Makiko Akiyama: Please tell us a little bit about yourself. Where did you grow up, where did you train, what is your current occupation?

Mikiko Minewaki: I was born in Akita prefecture in 1967 and grew up in Kitaakita, a city in a snowy, rural area of Japan. In high school I was good at math and chemistry and wanted to study behavioral psychology or industrial chemistry in college. But I ended up failing the entrance exam to my preferred university so I entered Hiko Mizuno College of Jewelry, a school I learned about by chance. Now I’m a lecturer there.

When you were a student, there wasn’t any department that specialized in art jewelry. And information about art jewelry was not as abundant as today. How did you get to know art jewelry in such an environment, and how did you learn?

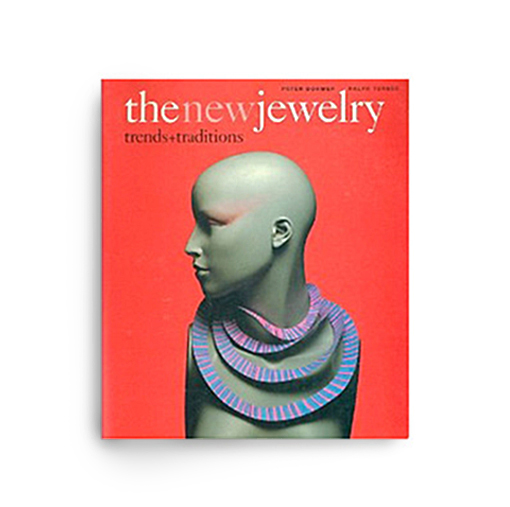

Mikiko Minewaki: I entered the course intending to become an in-house jewelry designer after two years of training. However, at the end of the first year, I learned that the college offered a class for third–year students to learn extensively about jewelry, including traditional techniques. Curiosity got the better of me so I joined the class and became acquainted with art jewelry thanks to Mr. Kageyama, the lecturer at the time. He handed me a vivid red catalog entitled The New Jewelry. It opened my eyes. The cover featured Professor David Watkins’s work, a spiral paper necklace colored with marker pens.

Where did you find information about this jewelry then? Where do you look for it today? Do you find it more accessible?

Mikiko Minewaki: When I was a student (1987–1989) the only sources of information were the catalogs from domestic and overseas exhibitions that my teachers showed me. There were also a lot of Schmuck catalogues. A few years later, the school started to invite artists from overseas to lecture, so I had more chances to listen to their stories in person (through an interpreter). I began to learn about the speakers as well as the artists they introduced.

Great artists such as Onno Boekhoudt, Otto Künzli, Daniel Kruger, and Bernhard Schobinger visited the school. The works they brought made me realize that seeing the physical pieces conveys more information than catalog photos. Their workshops showed me that their teaching methods were completely different from those of my class.

These days, I gather most of my information in person by going abroad to see the work directly.

You are known for cutting commodities into pieces and reconstructing them into jewelry. How did you find this unique way of making jewelry?

Mikiko Minewaki: I got the idea from the capsules known as gashapon. Students were making jewelry out of trash for a school project. I had some time to kill so I rifled through the junk and found a translucent yellow capsule, the type used to hold small toys sold in vending machines. At the time I was mixing wood glue with paint and letting it dry into sheets—exactly the same translucent color as the capsule.

So I took a saw to the gashapon without much forethought and ended up with a bean-like shape. The result—a translucent, yellow, bulging shape—was exactly what I had been toiling to create. It was mind-blowing to be able to create the shape I wanted simply by sawing. In that moment I had found my current style. Afterward, all I had to do was cut.

What sort of wearer do you have in mind when you create work? Does this “ideal wearer” resemble your actual clients?

Mikiko Minewaki: I don’t have anyone in mind. Come to think of it, I imagine that the wearer is me! My method is set in stone—it’s basically just cutting or refitting items I have on hand. The other aspects, such as the size, materials, and final look, are decided depending on whether it is something I would wear or if it is something I would want to own.

What kind of advice do you give to a student who aims to be a jewelry artist?

Mikiko Minewaki: Art gives the viewer new values, while jewelry gives the wearer the pleasure of having something on their body. Imagination is important for these new values, as well as making sure that the final shape is what you had originally imagined. Once you’re sure of this, you still need to ask yourself—am I happy with this? How far do I want to take certain elements? What does the piece need?

When it comes to freshmen, rather than tell them what to do, the first thing I ask is, “What do you want to do?” I try to be nice. Over time, I start to press them bit by bit to create works based on their own decisions, which satisfy them personally. This will help them find a point of view that allows them to face themselves.

Do you think there are any distinctive characteristics in art jewelry or jewelry in general in Japan? If any, what do you think they are?

Mikiko Minewaki: Artists from all countries give shape to ideas drawn from their living environment, point of view, philosophy, technique, experience, study, and research. The artist decides what elements to value. And their nationality steers this decision. So the difference between individual works will stem from the artist’s environment, be they from Japan or any other part of the world.

Speaking from my personal point of view or identity, the fact that I grew up in a rural area always comes to mind first. As a little girl I was surrounded by fields where I would weave white clovers into garlands and necklaces. This grew into my current desire to create jewelry from ordinary products. My mother and I only had common, everyday objects around us to play with, so we would transform numbers, letters, and scribbles into other objects, or draw on them to make them look like animals. This taught me how to find the object within an object. When I grew up I went on to study jewelry. This motivated me to find the form of jewelry hidden in objects—the end results being my current works. This perspective is not unique to me. I became good friends with several overseas artists because we share the same point of view.

Mikiko Minewaki: Studying jewelry taught me the joy of giving shape to my idea. This joy was enough to keep me satisfied for a while. My process involves cutting existing products into jewelry, so whenever I saw a new object, I would imagine ways to cut it. Some of these ideas were too large to create as jewelry. Or rather, the final product happened to be an object that you could call an installation.

For example, the Wii Fit balance board looks like a bag to me, so I followed my imagination and made it into a bag. This experience helped me realize that an object can be turned into something new without cutting it into pieces.

Working in other fields such as fashion and design has become a dominant notion in the international art jewelry scene today. Do you find this movement in Japan? If so, have you taken part in any such activities? And can you name an artist or two who succeeds in working within other fields?

Mikiko Minewaki: The character of my work has given me more chances recently to collaborate with people from product design or to cross the boundary between art and design. However, I think collaboration as such is still not a major movement in the Japanese jewelry scene. The idea is held back by the fact that contemporary jewelry had a low profile in other scenes.

Having said that, some contemporary jewelry galleries in Japan (gallery C.A.J, gallery deux poissons, and O-Jewel) have started to participate in art fairs in Tokyo, which they said received a positive response.

Last year, you were invited to build a temporary studio in a MUJI store and you taught a workshop. Can you explain what this event was like? And do you think it was a good opportunity for the broader audience?

Mikiko Minewaki: That’s an example of the collaborations I mentioned earlier. IDÉE, a shop that deals in original furniture and interior items, opened a program with the theme of “upscale.” Designers held workshops and set up open ateliers, and as their materials they used discarded product from MUJI, a home–furnishing brand that’s part of the IDÉE family. The resulting products were displayed at the IDÉE shop in Roppongi, Tokyo. This was a good opportunity for me to meet the store’s knowledgeable and informed customers, as well as professionals from different fields, as part of a grassroots effort to promote contemporary jewelry.

You always wear a lot of pieces of jewelry. How many pieces are you wearing today? Can you pick a piece or two and describe them to AJF readers? They can be either work of your own or by someone else.

Mikiko Minewaki: Today, I’m wearing 10 rings and four necklaces. I wear them always, not just today.

This ring is by Sakurako Shimizu, one of my students. It’s made of gold with a splintered surface.

I had asked my students to design and create a diamond solitaire ring from 18–karat gold. Her plan was to solder one pink, one white, and two yellow thin gold bars into a single bar, then round it into a ring and set a diamond. But when she went to bend the pink gold bar, it started to break. So she brought in new material thinking that the broken bar wouldn’t fit her design. But I was drawn to the broken bar. I suggested, “Forget your original design and think of how you can use this material.” And she went along with it.

So she incorporated the gold bar with the broken surface, set a diamond, and the ring was finally completed. Then she brought me a small ring and said, “I made another with the leftover broken bar, it might fit your pinky finger.” The ring was just big enough to qualify as a size 1 and it fit snugly. Since then, my pinky has become a target for students, and the rings on it keep piling up. Now it’s like a kind of display stage where rings come and go, but Sakurako’s ring has stayed on ever since I first wore it. She was my student about 15 years ago and still makes nice jewelry in New York.

But we were both fans of a Japanese band called Maximum the Hormone, so we searched their lyrics for the answer and for a suitable material. Turns out their song “Nitro BB Sensou” sings about BBs. We knew that we had found our material. The material didn’t have monetary value but it had value as an important motif in the lyrics of his favorite band. Once he was able to accept it as a building material, his excellent skill made the rest easy. I’ll never forget him, a guy as big as a sumo wrestler, as he pinched and drilled tiny BBs one by one. Memories aside, I’ve kept the necklace on since then because it’s such a cool item. It’s been a good advertisement for him and has brought people to his work. It makes me happy to wear this necklace with Otto Künzli’s 1 Cm of Love.

What do you base your decision on when you buy a piece of jewelry?

Mikiko Minewaki: The point is if I really want it or not. Sometimes it’s the concept, other times it’s just because the item suits me. There’re all sorts of reasons to wear jewelry. I like works that allow me to interpret them in my own way, which then tells a story to others.

For the body, jewelry is an absolutely foreign, obstructive, and nonessential object. But, at the same time, it’s a thing of value that people are willing to accept despite this. (Some people go so far as to pierce their bodies just to wear jewelry).

I think contemporary jewelry is interesting in the way it shows new value for jewelry, be it in terms of technique, material, form, size, or how it’s worn on the body. I make and wear jewelry in the hope that I can introduce different values and points of view to expand the imagination of the viewer and broaden their understanding.

Mikiko Minewaki: The World’s Slaughterhouse Tour, by Junko Uchizawa (Kadokawa Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd). This illustrated report introduces slaughterhouses from all over the world. I picked it up because the act of dissection reminds me of the way I make jewelry. My grandfather was a farmer and when relatives got together he would prepare the chickens that he raised. I was always interested to see how he gutted them. The title may be a bit shocking, but the book deals with serious subject matter, including spiritual and cultural issues, life, family, technique, respect, awe, and more.

Seidosha Inc., Eureka Special: Heisei Kamen Rider. I can’t live without tokusatsu heroes. Their heroic world-view has been with me since I was a little girl. Tokusatsu heroes have a huge impact on the economy—aside from the shows themselves, there’s transformation belts, card games, snacks, cakes, and even curry and sausage!

This book isn’t a catalogue of photos for children to enjoy, but rather it’s an analysis of the history of Kamen Rider from the perspectives of the scriptwriters, developers, and actors. It might seem strange that adults like me get hooked on a TV show for kids, but I get sucked into the heroic world it creates. There’s always an item that they use to transform, and last year we finally got a Kamen Rider who uses a ring.

To go off topic a bit, I was asked to be an advisor on the show and gave technical assistance to the actors as well as instructions about what kind of workbench and tools the ring artisan should use. It was so exciting! The series has since ended and it had the highest recorded viewership of any of them to date. I hope the kids who watched it have positive feelings towards jewelry when they grow up.

The last book is the one I’m reading now: Wakaki Hi ni Bara o Tsume (Pick Roses While You’re Still Young), by Jakucho Setouchi and Shinya Fujiwara (Kawadeshobo Ltd). This book is a series of correspondences between Jakucho Setouchi, a nun and writer, and Shinya Fujiwara, a photographer and writer. As opposed to e-mail or text messages, I enjoy the luxury of selecting words carefully to write by hand and send as a letter.

Translation assistance and editing by David Kracker

Index Image: Mikiko Minewaki, work in progress (fruits basket) in the artist’s studio, 2013, photo: artist