Almost all the elements for greater recognition save one (a national or even regional tour) are in place for Hu with this survey: loans from major private collections and East Coast museums; big-name art critics and curators to author the catalogue essays; an elaborate, gorgeously designed full-color hardbound monograph and a major art museum venue. (Bellevue is now among the top ten decorative arts museums in the United States.) As we shall see when examining these elements, other surprising aspects have also been included in the mix — some good, some bad — that alternately reinforce and detract from the artist’s reputation. The catalogue contains essays by Jeannine Falino, curator at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York and Janet Koplos, craft historian and art critic. Each work in the exhibition is reproduced in color, with most accompanied by an extensive autobiographical note and technical explanation written by Hu.

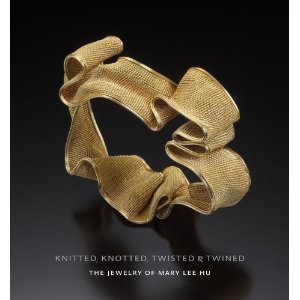

The overall effect of the exhibition design was one of restrained theatricality. Since gold is so shiny, it does not require much other than simple, secure display presentation with clear supports and stands, so the visitor can see all sides of each necklace or bracelet. Shimmering and beautiful, there was also an anthropological or artifactual atmosphere, as if all the objects were from a magical ancient culture, like the Scythians. Contained in one large room, the retrospective hypnotized viewers, many of whom were young people who made multiple visits and spent hours studying the art.

This is a startling claim and one that Hu told me when I spoke to her recently that she regretted not protesting before the text was published. Where was the bravery of the tenured faculty artist who is free to do as she wishes because her income is guaranteed? Was this a case of an artist wearing golden handcuffs, i.e., the luxury, comfort and stability of a fulltime teaching job? Did the comfort of the handcuffs outweigh the urge to continue making work that might not sell?

When I spoke to Albert Paley about Hu, he defended the special case for artists using gold. “Jewelry has always straddled one-of-a-kind pieces and production pieces. For every Fabergé egg, there were thousands of steel cigarette cases. You can call it art jewelry, but it straddles both worlds. You need the wearer to provide the context. The goldsmiths’ group is the most financially driven of all the crafts. It’s a real issue. You either meet the marketplace and water it down, or you stop doing them. Hu has always been an active professional who despite all this continued to focus and devote herself to her work.”

While hardly “watered down,’”Hu’s subsequent twined gold necklaces and cuffs gained greater market and museum attention as they continued to develop in nearly every significant way — color, line, scale —except innovative form or the radical risk-taking of Forms #1-3.

Returning to the catalog, Janet Koplos’s essay “Rewards of Constraint” provides a superb contextual backgrounder to Hu’s achievement, but is weak on regional analogies, parallels and influences. It’s all very well to mention craft pioneers Hu was fully aware of before Seattle. Paley, Fisch, Richard Mawdsley, Marjorie Schick, Alexander Calder, and the Pijanowkis are all duly noted, but her important relationships to University of Washington teachers Ramona Solberg and John Marshall, along with her influence on ex-student Flora Book go unmentioned. This is a pity because Solberg’s shared affinity for South Asian art and travel are significant and Marshall’s insight in hiring Hu to teach at the university seems worth examining as a valid part of American craft history, something in which Koplos is now seen as an expert. As John Marshall said to me when I asked him about why he hired her, Hu ‘was very solid, very traditional, with a really genuine sense of the craft. She played a strong role as far as detail goes. All of her work was done with precise finish.’ Koplos goes on to namedrop New Yorkers David Smith, Ibram Lassaw, Herbert Ferber, Theodore Roszak and Richard Lippold, none of whom (except for Smith) Hu was familiar with.

How can Hu criticism and commentary improve after the super-supportive, cooperative chronicles of the catalog co-authors? After all, with scant serious analytical writing about her, most coverage has been, in her words, “descriptive.” To that end, let us conclude by suggesting a few lines of inquiry for the art critics and art historians of the future to pursue.

One other prospect exists for Hu, according to Lloyd Herman, is designing for industrial or limited mass-production, something with which European craft artists have long been comfortable. This democratizes art and makes it more accessible. Hu’s designs would be unusually beautiful and more affordable. As Herman said to me, “Like that project at Reed and Barton (silversmiths) in the 80s, she could create something that could be industrially produced.” That way the elite modernism of luxury goods could be dovetailed with the postmodern privileging of design over the handmade, adaptation of traditions and the risk of unexpected outcomes.

When I spoke to her, Hu was pondering her next steps. “I hope my work is going to take a jump. Now that I’m dealing more with form, I’m trying to push more ways of creating it.’”Whichever route Hu takes, it would seem she is on the precipice of another “jump.”