“Hello World. It’s us.”

Thus opens, with typical paper-sword-rattling, Overview magazine’s sixteenth issue (and first paper edition), launched in Munich to celebrate Wunderruma and the small invasion of New Zealand makers that came with it. (The publication is written, typeset, and distributed by the Jewelers Guild of Greater Sandringham. It is free. It is uncensored. It is apparently running on beer and crisps. It also blatantly lacks a masthead. The organization is probably too polymorphic, or too underground, to deal in names. But should heads be tentatively nailed to that mast, let’s bet that Kristin d’Agostino, Sharon Fitness, and Raewyn Walsh would be staring down it.) Anyway, it hit the carpeted floor of the Schmuck pavilion with a thud! and soon became the talk of the fair. Fingers started to point in the general direction of the Netherlands, and the word on the street was that Liesbeth den Besten had turned her critical beamer on the “mecca” of jewelry and was giving this field’s conflicted relationship to wearability and the user a good seeing to (André Gali, from Norwegian Crafts, puts den Besten’s texts eloquently in context in this recent article).

We are very proud to have Liesbeth den Besten on the board of AJF. While we appreciate that the field of contemporary jewelry is not (and possibly won’t ever be) as securely established as other craft fields, it certainly has outgrown its reputation as a marginal blip on the arts map, and we share Liesbeth’s opinion that the field—now approaching 50-years-old—will benefit from dissenting opinions and constructive criticism. So, we kindly asked her if she would let us reprint her pamphlet. She would. It has been very slightly modified from its original version.

Ben Lignel, Editor

The Golden Standard of Schmuckashau

Liesbeth den Besten is looking forward to the kiwi invasion of Munich and summarizes the “golden Schmuck standard.” The essay is based on her 2013 Zimmerhof lecture.

Schmuckashau—this is the word I encountered recently in a text by Australian critic Vincent O’Donnell, reviewing Robert Baines’s publication Fabulous Follies, Frauds, and Fakes (2013). In the review, the notion Schmuckashau stands for the highest in contemporary jewelry. According to the reviewer, ‘the revered Schmuckashau has for five decades arbitrated taste in art jewelry.” The reviewer continues to tell that Australian Robert Baines is a celebrated Schmuckashau attendee for many years, who even was awarded the prestigious Herbert Hoffmann Prize.

Schmuckashau, the word the reviewer uses, refers to the old name of the jewelry event in Munich, which was once addressed as Schmuck Schau, which literally means “jewelry exhibition.” Today, it is simply called Schmuck. But in English, the word “schmuck,” which is spelled the same way but without a capital “S,” has a rather questionable connotation. It is slang, used for penis and for an obnoxious or contemptible person—a difficult word to use in English and very remote from jewelry. Schmuckashau is a wonderful invention. It is contemporary jewelry language in its purest form, a mixture of German and Aussie-English, a phonetical monster that gains magical power because of a combination of incomprehensibility and the values it stands for. It summarizes the many miles of distance and misunderstanding between the continents, between the presumed center and the assumed periphery, between those who are initiated and those who are still longing for a rite of passage to Munich, the so-called center of the world of contemporary jewelry.

Every year, we can watch the numbers of this jewelry growing. There is more Schmuckashau now than there has ever been before. It comes from every corner of the world, for the most part. It is completely interchangeable, which means that the work doesn’t give you any clue as to where it originates from. For the in-crowd, it is instantly recognizable as contemporary jewelry.

A language has developed, a vocabulary based on recycling, copying, and assembling. Today, we all speak jewelry—a language that is established and confirmed at the yearly jewelry “mecca” in March, the big social jewelry-community gathering, the network magnet, the exhibition machine.

But, I am a little bit worried by this idiom, by people speaking jewelry. One of my main concerns is that contemporary jewelry has become a fait accompli, a matter of fact, a this-must-be-it experience, and nobody is asking questions anymore. Well, Nanna Melland did ask questions last year. Her Swarm, consisting of hundreds of small airplanes in different sizes, was the first piece ever that, in the decades-long history of Schmuck at the Internationale Handwerksmesse, was shown outside the showcase. People could actually buy a part of the installation during the show. But isn’t it crazy that a work like hers, how much I love it, is observed as something outrageous within the context of Schmuckashau? As a matter of fact, it tells more about the supposed golden standard of Schmuckashau than about where contemporary jewelry has arrived today.

During the Schmuck event, jewelers can test their ability to temporarily present jewelry in the city. With very few materials, and sometimes very little costs, places that are not really made for it are temporarily occupied by jewelry, jewelry out of the showcase, such as an antiquarian bookshop, bowling alley, church (the Swedish), Orangerie, restaurant, and foundry. Some exhibition scenographies are so well done and so beautiful that they are better than the work shown or better than the exhibition’s concept. In Munich, you can encounter beautiful titles and beautiful displays yet the reasons for bringing the work of different artists together in one exhibition is often completely unclear. Is it because they are good friends, because it is fun to see each other and work together for a couple days, because they know this space and want to be present in Munich? Often you wonder, was there any reason to make this exhibition? Munich during Schmuck offers too many examples of bad curating, where good pieces of jewelry become props in a wonderful setting.

Last year Die Ausstellung (“The Exhibition”) was programmed as the mother-of-all-exhibitions, the event you shouldn’t miss. Although there is probably some irony in the title, we should take care. Die Ausstellung is Professor Otto Künzli’s overview of 45-odd years of working in the field of contemporary jewelry compressed into about 80 showcases.

Otto Künzli is a main figure in the contemporary jewelry world. As a smart as well as sensitive conceptual artist and as a teacher, his contribution to the field is invaluable. Künzli has been one of my jewelry heroes from the moment I became interested in jewelry in the 1980s, and I have seen many exhibitions of his work, in galleries and museums, since then. The reason for my enthusiasm about his work is his way of looking at jewelry, exploring its limits and unveiling its ethics, making un-wearable jewelry and invisible jewelry (such as the gold bullet for the armpit) as well as jewelry everyone wants to have and wear. Through his work, Künzli was able to stretch my ideas (and not only mine, of course) about jewelry and the body, for instance through his jewelry that literally connected two people. His work is rich, complicated sometimes, at times humorous, and often I was completely seized by it.

Die Ausstellung, however, was rather disappointing to me. I will try to explain why because it has to do with my ideas about this so-called “standard” in contemporary jewelry. The exhibition setup was a typical Otto Künzli design, with a mass of showcases seemingly scattered through the room at random. People who visited the exhibition Des Wahnsinns fette Beute (2008), about the Klasse Künzli, know what I mean.

Here, like there, the numbering of the showcases followed no rational path, and we could again watch visitors nervously looking through the exhibition’s handout, turning it over again and again to find the number they were looking for. We have seen these scenes before—and since, in the new setup of the Danner Rotunde in the Neue Sammlung. This is Otto Künzli’s vernacular, his very own exhibition idiom that follows its own rules, logic, and humor.

The scary New American Flag on one wall was good to finally see in reality. It is an impressive piece of cloth, merging three popular American symbols into one very powerful and aggressive image that determines the atmosphere in the room to a certain extent. For the average, non-initiated visitor, this flag may be very confusing and controversial. What does it have to do with the exhibition, the rest of which is only about beautiful aesthetic objects in showcases. Where is the connection with the flag? Why was that flag hanging there? Where is the story?

Insiders could rejoice to see, in reality, all those pieces they only knew through images, and for some people, this was like some sort of spiritual encounter. This is what the New Zealanders wrote about in their Overview magazine: “All those Ottos we know and love in one room; the Red Dot, One Metre of Love, Oh Say, the postcards, the Ring for Two Persons, Gold Makes Blind, the Mirror Glasses, the Mickey Mouse heads, the importance of being there.” Hmm … the importance of being there … maybe this sums up the meaning of Die Ausstellung the best way.

Because the Otto Künzli exhibition lacked any further documentation or information, the objects were pulled back in their objecthood. It was as if looking at the images in a book or on the Internet. They had lost all life. They became mere objects—cuttingly sharp, shiny red, highly polished, symbol-like, but completely flat and even disconnected from people or the body. His famous chain, composed of 48 re-used wedding rings, missed this contextual information cruelly.

What went wrong here is that all the attention of the curators of the exhibition was focused on the objects. But Otto Künzli’s work is not a sum of objects at all. It is, rather, a continuation of projects, processes, stories, and concepts. The wedding-ring chain was the outcome of a project and a process Künzli went through. First, there was the idea, then there was an advertisement—“I collect wedding rings”—in a local newspaper, repeated 10 times in 1985, and then came the reactions. Künzli not only collected all those used wedding rings but also the stories of the owners. By leaving them intact and only cutting through them in order to be able to connect them, Künzli connected the personal, mostly sad, histories of many individuals. Therefore, it is a contemplative object. But in the exhibition, this chain, stripped of its stories and background, was reduced to merely an object. Only the very well informed viewer knows how to appreciate this object.

Otto Künzli is also famous for his photographic series as a means of artistic research, but there was no evidence of this, apart from a small selection of photos from the Gallery of Beauty series. And so, the exhibition was a collection of objects that were ripped of their context and emotional content, bypassing the stories, the processes, and the artistic photographic research —and this is exactly what makes Otto Künzli’s artistic career so singular and so important.

I cannot help but think that this focus on the aesthetic object is a very deliberate choice, but I have been racking my brain about why the exhibition was curated like this. The only reason I could find is this—the exhibition wanted to stress the perfection of Otto Künzli’s work, or as the introduction text to the exhibition reads: “Objects with a clear, minimalist appearance, captivatingly crafted to perfection, and highly visible—jewelry that adorns and at the same time possesses an autonomous aesthetic status of its own.” The presumption is thus: we don’t need to add more information because this perfect work speaks for itself, not only as jewelry but even more as autonomous art objects. Maybe this is true. Maybe the work does speak for itself, indeed. Maybe it speaks an art language, maybe it speaks jewelry, but the language of jewelry is highly self-referential, and outside the small circle of speakers, nobody understands. The average uninformed museum visitor must have felt lost between the many showcases.

Die Ausstellung showed me how objecthood excludes jewelryness.

Objecthood excluding jewelryness—this is what happens everywhere in Smuckashau. Schmuckashau is a monoculture of beautiful (although not always), wearable (well, in principle) objects that are completely frigidly exhibited in well-designed displays. It forgets about its users, the wearers, the humans that like to wear jewelry. Sometimes, it looks as if these objects do not even want to be worn. Jewelry has developed into a correct language—highbrow, not for dyslexics, stutterers, and persons with a different language and background, not for the foreigners, and especially not for wearers. I would like to make a plea for less coherence, for more distortion, for more confusion and more discussion, for less finished objects exhibited in wonderful places and for more open ended works, for less gallery-imitating presentations and more happenings and events in the streets, subway stations, the fair, and shopping malls, and for more efforts to have jewelry on the right spot—on human beings.

At Schmuckashau, we have created our own bubble where everyone knows each other and everyone likes each other but nobody else knows us. The city of Munich is completely blank about what’s going on. Other people have no idea that thousands of people from all around the world get together in their own Munich comfort zone each year in March to celebrate jewelry.

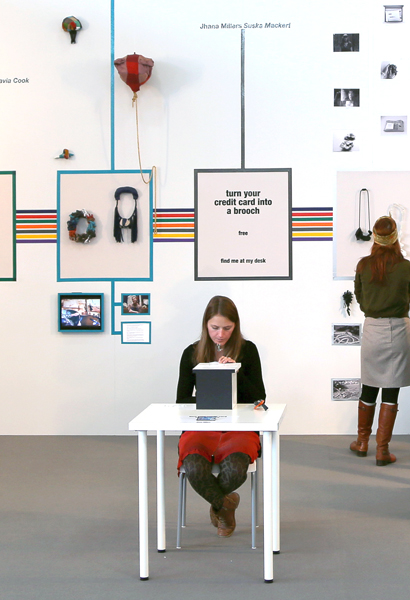

As a matter of fact, the Handshake project—a mentoring project with young mentees from New Zealand and tutors from all over the world and the brainchild of Peter Deckers—was one of the very few innovative projects that participated in Munich. It was innovative because of the collaboration between mentees and mentors via Internet, Skype, and blogs, and also because the final show involved some work that was made on the spot or was open ended. Jhana Millers, interested in value systems, continued her project This Brooch Cost Me My Credit Card, inviting people to donate a credit card that she converted into a brooch on the spot. And Sarah Read introduced the Home from Home open call, inviting visitors to step out of their usual routine and invite an artist—Sarah Read—into their home for a three-day residency.

By the way, New Zealanders, kiwis, are wonderful people. They have a great sense of humor, a lovely lifestyle, and they are struggling with their isolated position somewhere halfway between Australia and Antarctica. I’ve been there twice by invitation, and I was amazed by the eagerness of New Zealand jewelry people to know more and to become part of this global jewelry scene. Because they lack direct connections with the supposed jewelry centers in the world, they developed their own infrastructure and a kind of out-of-the-box thinking.

A good example is The See Here, a window gallery in Wellington where exciting events and presentations take place. The invited artists can do anything they want in this shop window. In 2012, Sarah Read decided to do an artist-in-residency at The See Here under the title “Look, no hands: a creative retreat.” She wanted to work there simply as an artist but without knowing where it goes. First, she had to deal with the fact that she had to work under the public gaze. Then, she had to occupy the window space, and finally, she spent her time (one month) reading, thinking, working at her workbench, interacting with passers by, and receiving visitors.

Another Sarah Read project involves co-creation with other people. In response to the February 2011 earthquake in Christchurch, she sewed simple and colorful ribbons with the text “this too shall pass.” They were made in collaboration with other people and sold for 10 NZ$ to support The National, one of New Zealand’s vanguard jewelry galleries, which happened to be in the red zone of Christchurch, the area that was most affected by the earthquake and had to be cleaned out in a few hours after the catastrophe. All of Read’s work has to do with jewelry or adornment, but she prefers to collaborate with others instead of the isolation of her studio.

During the last big jewelry event in 2012, called JEMposium and organized by Peter Deckers, some artists introduced the Jewellers Guild of Greater Sandringham—a name with a wink—to a larger audience. Sandringham is a rather undeveloped, multiethnic suburb of Auckland, not very well connected to the city center by a rather poor public transportation system. So, the name Guild of Greater Sandringham underlines isolation within isolation. This group of enthusiastic jewelers started a Facebook group and produces a wonderful and very informing Internet magazine every few months. Started as a need to connect and to keep each other updated in New Zealand, it has become my lifeline with New Zealand all the same. And now, they presented their first printed issue in Munich during Schmuck.

It is interesting to see that refreshing ideas, ideas that make us think differently about issues such as value, studio, and uniqueness, now seem to come from far away, from the periphery, and that the center is stuck in the formal standards of Schmuckashau. This is my reason for referring to them: the New Zealand view on contemporary jewelry provides us with a peripheral view, the view from outside, the mirror that is hold up to our face, and the view that is missed so much at Schmuckashau.

This year, New Zealand was represented in Munich with Wunderruma, an exhibition curated by Warwick Freeman and Karl Fritsch in Galerie Handwerk. I wondered if they were able to avoid Schmuckashau’s traps. Well, not completely, I have to admit. They had to deal with the reality of the Handwerkskammer, so the main part of the work was exhibited in regular showcases, but their curatorial choices were surprising. Freeman and Fritsch made interesting groupings, mixing young and old, historic pieces by grand old men (such as the Swiss goldsmith Kobi Bosshard, who settled in New Zealand in 1961, introducing modernism), new work made by ambitious unknown young makers, and work by artists without a jewelry practice, while also some examples of Maori pieces from museums in Auckland and Munich and historic colonial jewelry were included. I imagine the choices made by the curators have met with frustration and discussion in New Zealand. They did not choose the work artists are famous for, but instead sometimes took pieces that are much less known but fitted in the curatorial discourse. The New Zealand exhibition showed that it is possible to make jewelry that is dependent on place, culture, and crafts traditions within the parameters of contemporary jewelry. Alan Preston’s Gannet Feather Necklace and Louisa Humphry’s Headdresses combining straws, plastic, and plant material with traditional weaving patterns are alternatives to fusion-kitchen global jewelry.

Most of all, I loved the non-dogmatic and subversive vision of the exhibition makers. Wunderruma is an exhibition without heroes, icons, or an over-emphasis of the individual artist, but it is truly about jewelry, about necklaces and brooches, about rings and ornaments, clearly and convincingly from another culture and another continent. The kiwis appreciated jewelryness above objecthood.

I would like to finish this essay with a manifesto for contemporary jewelry.

- Forget about sceneries and props.

- Forget about objecthood, focus on jewelryness.

- Forget the aficionados, target the uninitiated.

- Focus on the ‘”why” and “how” of jewelry, on people and jewelry.

- Focus on questioning instead of answers.

- Focus on experiment instead of nice results.

- Focus on process and projects.

- Focus on inclusion of other media and strategies.

- Focus on sharing and collaborating.

- Forget the unique one-offs for the gallery, every now and then try multiples.

- Take care of finding your own vernacular. Use slang when necessary.

- Forget about Schmuckashau.