India makes a convincing claim to be the centre of global jewelry. Last year, the international gold market was sustained by the annual marriage season in India, featuring ten million weddings crowned in gold. Not only the world’s largest consumer of bullion, the subcontinent also has the largest diamond cutting and polishing centre in the world – Surat in Gujarat. It boasts a highly sophisticated and seemingly inexhaustible tradition of body ornament. As an emerging superpower, India will only increase its lead as the world’s largest jewelry economy.

How can all this wealth support jewelry as an art practice? What does contemporary jewelry in India look like? In February this year, India hosted Abhushan, an international jewelry summit. Surely here we’d find the answer to this question.

The Crafts Council of Chennai has been extremely active in jewelry development. In 2004, they helped organize a series of events titled Grass to Gold, which extended the view of jewelry in India beyond precious metals to include materials such as terracotta and coconut shell. In 2008, Usha Krishna from the council was appointed president of the World Craft Council, a platform from which she has staged an ambitious sequel, Abhushan (‘ornament’ in Hindi).

Seed to Silver was installed in Ashok Hotel, a gleaming marble building dedicated to high-level government business in downtown New Delhi. Setup was a herculean task. The plucky management team was under enormous pressure to put on a comprehensive display of world jewelry with less than a day to install the exhibition. It was an impressive arrangement. The pre-fabricated cabinets were charming, utilizing bamboo and strewn with organic material. This tropical design provided an immediate recognition of the ‘seed-to-silver’ theme, promising a fresh new aesthetic appropriate to an Asian context.

But old habits proved hard to break. Ironically, the tropical design ended up being compromised by the hegemony of northern jewelry. The European and North American works looked at home in their spacious displays, but unfortunately the southern collections, particularly from Africa and Asia-Pacific, were crammed at the end. This is not to fault the team, who did their best given lack of time to lay out the exhibition beforehand. But the opportunity was missed to question the default hierarchy of global contemporary jewelry.

Another intriguing omission was the host country itself. While the contemporary jewelry on display originated from all the world regions, India itself was represented exclusively with tribal jewelry. Elsewhere in Asia, I was pleased to find a bold new generation of contemporary jewelers emerging from countries like Indonesia and Thailand. The traditional Indian pieces were quite stunning works in silver that certainly commanded their place, but it did raise the question: does Indian contemporary jewelry exist? Surely it must. Maybe our concept of contemporary jewelry is too limited.

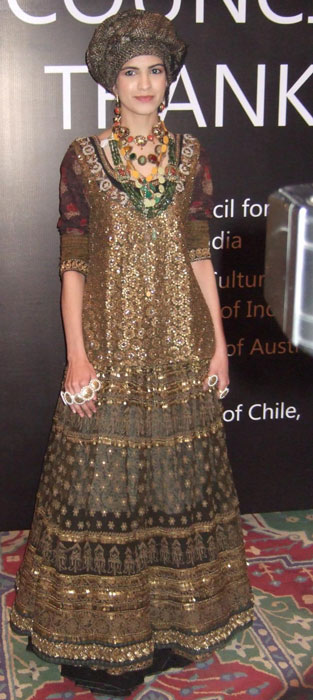

As part of the formalities on the first day, one minister proclaimed, ‘The power of the south is here!’ He wasn’t referring to the global south, but instead to the distinctly regional elegance of the occasion. The Tamil-speaking organizers ensured that the event was conducted according to Carnatic standards. Every session concluded with an elaborate ceremony as speakers and chairs were adorned in swathes of sumptuous textiles in honor of their participation. Abhushan organizers put to shame the predictable ‘would you join me in thanking . . .’ routine that belabors most conferences.

In terms of content, it took a while to engage with a story of jewelry that matched its stated social aims. It was hard to resist the lure of luxury. Savvy Indian jewelry designers celebrated the fashion for vintage Moghul, featuring lavish neckpieces cascading in glittering gems. For a while, the earnest talk about social consciousness seemed like a political sideline.

But after this wave subsided, we were left with question of where to locate Indian contemporary jewelry. During the summit, Indian contemporary jewelry practice was discussed in the context of artisan production. Six of the foreign jewelers participating in the talks had also taken separate workshops where they introduced new techniques to Indian artisans. The ubiquity of artisans in India is at odds with the studio-based nature of the contemporary jewelry movement. During the conference, Helen Britton presented a beautiful talk about her own exploration of materials, reflecting on personal stories of discovery. This is an experience denied to almost all Indian contemporary jewelry designers, for whom contact with materials is largely delegated to others.

While this seems an obstacle to India’s role as a potential player the contemporary jewelry scene, it does raise the question in the opposite direction. Must contemporary jewelry be an artist-made phenomenon? Is the artist at the bench, experimenting with materials, the essential crux of creativity?

For a culture that maintains a division of labor between creativity and production, there seem to be two potential paths towards Indian contemporary jewelry. One is for jewelers to abandon their workshops and get their hands on the materials themselves. This would be to adopt the Western model of studio practice. The other is to make its distributed production essential to the meaning of the work. This is most obvious in the ethical dimension. While much of the Abhushan audience was dazzled by the splendor on display, a distinguished Indian woman continued to question the conditions of the artisans who actually produced the work. Each workshop offers itself as a microcosm of the broader economic order. Thus Indian contemporary jewelry could embody in its production ethical values about social relations.

We are already seeing the impact of ethics in the jewelry scene. This isn’t just limited to art movements like Ethical Metalsmiths. On High Street there are new accreditation standards like that for ‘white diamonds’ whose production is innocent of the kind of corruption that siphons money to the arms trade. Likewise, the concept of Fair Trade gold is currently focused on the conditions of miners. But there is no reason why it might not extend further down the supply chain to jewelry production.

But there are problems with accreditation. While it can increase the value of the jewelry product, and strengthen consumer confidence in the story of its origins, it does not necessarily have a particularly creative benefit. But it is possible to take the ethical a little deeper and focus on artisan traditions, drawing particularly on techniques that are languishing? The act of recovering a tradition can be both a commitment to cultural sustainability and a creative act of interpretation, parallel to re-invention of jewelry in contemporary practice through incorporation of new materials.

The ethical dimension can also extend beyond the domain of production into its use. In Indian culture, jewelry has a powerful role in defining differences of gender, caste, religion and age. From the sidelines of Abhushan, it was possible to glimpse how contemporary Indian jewelers might explore this ritual dimension. A designer gallery had been set up as a commercial space for product promotion and sales, in which I found a number of art jewelers from Kolkata. While busy with product sales, they were happy to show me images of their art work from under the counter.

Of course, artists these days are not limited to opportunities in their own countries. There is no reason why we will not soon be seeing Indian contemporary jewelers like Ahluwalia in international jewelry exhibitions. But I wonder how well they will fit? Settings like Schmuck focus on the object, largely independent of context. To appreciate what’s emerging beyond the West may require alternative formats, even runways.

Thanks to the visionary organizers, Abhushan put India into the global jewelry scene. In doing so, it set a challenging new horizon for contemporary jewelry. As in geopolitics, the emerging economies are straining the existing global hierarchies. Constraints to freedom can be found both inside and outside the Global South. But the contemporary jewelry movement has everything to gain by these international re-alignments.