The international critical discourse on art jewelry is still not consistent with the use of labels (art – author – studio – contemporary – research jewelry) but the meaning is clear. ‘Just as the rectangular canvas was freed from representation and became an arena for the exploration of a range of other themes, so has jewelry become a device for conceptual exploration and personal expression.’ (Metcalf) ‘The value of contemporary author jewelry is not to be found in its costly material, but in the special relationship that an artist has with his/her work which makes every piece an individual artefact.’ (Den Besten 35) ‘Poised between high-street jewelry and art (the former’s glorified other, the latter’s poor relative), we know what it’s not (‘just’ manufactured artifacts for wearing), and what it wants to be (the expression of individual talent that reflects on, and sometimes influences, contemporary culture).’ (Lignel) ‘The term that I use, ‘research jewelry,’ would tend to focus on the approach to jewelry as a testing and investigation ground and at the same time to step over the complicated labels of art or artist. (Bergesio 126)

Spreading the culture of art jewelry all over the world is an ongoing battle, even if it has already been historicized, exhibited and kept in museums and has become the protagonist in many exhibitions, fairs, conferences and publications. Italy is much more reluctant to allow jewelry the possibility of being a free creative expression, free to develop and interpret the spirit of the moment. In Italy, proposing jewelry as a creative medium of expression provokes stonewalling: the jewelry world doesn’t consider it jewelry and the art world doesn’t recognize its creative research value. Even though in recent years new events and exhibition spaces nationwide have been added to the historical activity of the council and galleries in Padua, the Italian panorama in relation to the promotion of research jewelry remains lacking.

Jewels Signed by Visual Artists

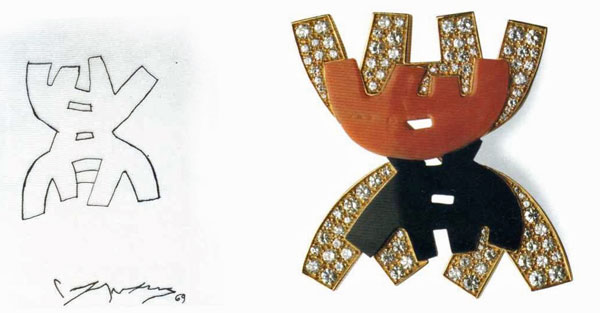

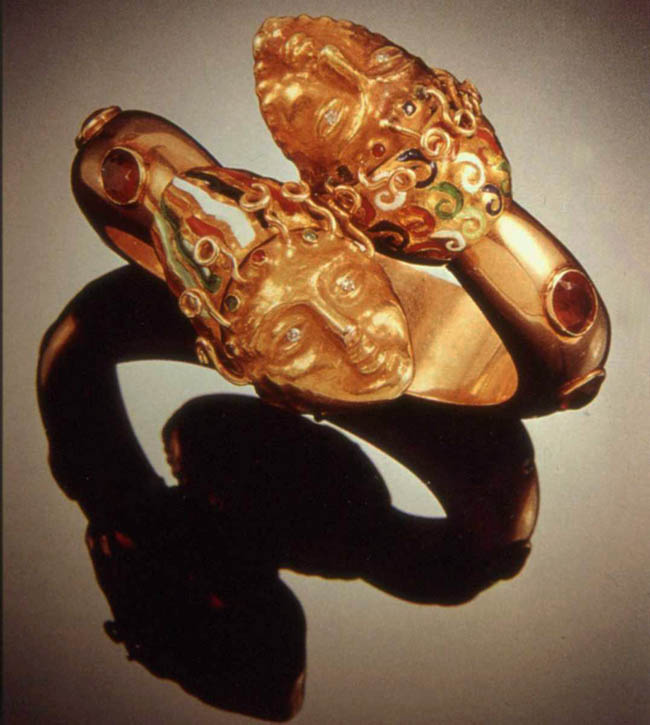

In Italy, from the end of the 1940s until the 1970s, we can identify a sort of intellectual fashion, which focused only on this theme and ignored the research of people totally devoted to jewelry. During those years, but also in recent times, a large number of publications, articles, exhibitions (the last of which was held in 2008) dealt with jewelry by artists, pieces signed by famous painters and sculptors, which were welcomed as an expression of the rebirth of the goldsmith’s art. Although it is not only an Italian phenomenon, for nearly three decades it achieved an incredible popularity in Italy.

The first Italian to involve visual artists in the creation of jewelry was Mario Masenza. After World War Two, in the elegant jeweler’s shop Gioielleria Masenza in the heart of Rome, he presented these new jewels next to the traditional ones. (The first exhibition dedicated entirely to jewelry by visual artists was organized by Masenza in 1949 at gallery Il Milione in Milan.) In the early 1960s, also in Rome, Danilo and Massimo Fumanti, members of a family of historic jewelers, decided to invest money and involve artists to increase their production. In 1967 in Milan, Giancarlo Montebello and his wife Teresa Pomodoro started to produce jewels in small series designed by painters and sculptures. (Bergesio 302) Art galleries began to commission jewelry from their artists to be sold alongside the paintings and sculptures.

Only Visual Artists Can Create Art

Outside Italy it is more common to find nuanced judgments on this point. Writing in 1961, Graham Hughes wrote that ‘This is sometimes called artists’ jewelry but that is misleading: the point of the exhibition is to prove that all good jewelers are artists, to diminish rather than increase the gulf between the different types of jewel.’ (Hughes) Or as Ralph Turner put it in 1976, ‘It is a common mistake to assume that an artist who is painter or sculptor can necessarily create a work of art in jewelry. The medium is a difficult one and requires an attitude of mind, combined with technical skills that are not to be acquired overnight.’ (Turner 24-25). In Italy, the attribution of artistic validity seems to follow this equation: art jewelry = jewelry by painters and sculptors. This misleading concept became a dogma and contributed to the division between the idea and its realization, bestowing only on a visual artist the power to transform craft into art.

Seeking An Origin for the Dogma

I’m keen to suggest that behind this sectarian way of conceiving art we can identify the idealistic vision of ‘art as pure intuition,’ founded by the most powerful Italian philosopher, Benedetto Croce. According to Croce, the work of art is a mental phenomenon, free from use and technique. Demonstrating the strict judgment on technique by the neo-idealistic vision of the aesthetic work, Croce wrote: ‘The technical does not enter into art, but pertains to the concept of communication. . . . We must condemn as erroneous every theory which confuses aesthetic with practical activity. . . . Art is thus independent of science, as it is of the useful and the moral. . . . Technique is certainly not a special activity of the spirit.’ (Croce)

Croce’s influence became deeply integrated into Italian culture partly because it permeated the educational reforms of Giovanni Gentile in 1922–1924. Gentile was a philosopher and a pedagogue, who shared with Croce the same idealistic vision of culture, what he called ‘the spirituality of culture.’ His reforms separated strictly aesthetic education from technique (Liceo artistico – Istituto d’arte) intellectual work from manual work and declared the primacy of visual arts over craft. Consequently, it is totally understandable that the heated debate about arts and crafts that took place in Italy in the 1920s found its way into the mainstream, promoting the view that only visual artists could renovate the craft industry. In 1932, in the esteemed magazine Domus, the architect and designer Giò Ponti stressed the need for artists in the fields of manufacture ‘not only for the taste renewal and fresh air of cultural contacts, but especially for the invention.’ (Tonelli 128)

This statement confirmed the activities of E.N.A.P.I. (in English, the National Board for Craft and Small Industries) a state institution founded in 1925 to renovate Italian crafts through the participation of visual artists, who provided drawings for projects in ceramics, embroidery, jewelry and leather that were executed by craftspeople.

From this prospective it seems obvious that the jewels by visual artists received a lot of attention as a product with a certificated artistic aura. The activity of art jewelers remained in a shady area of culture, penalized because they were located in the craft world.

A Remarkable Change

Conclusions?

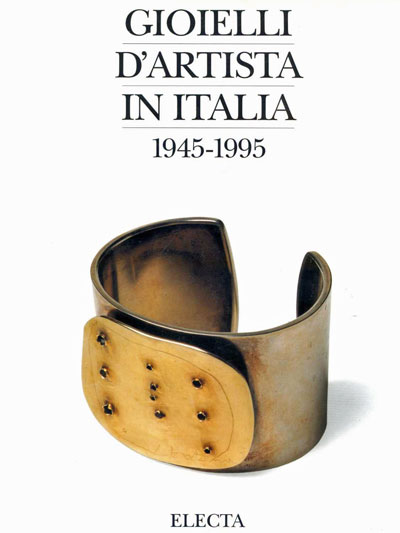

In 1997, when I was working on my thesis, which dealt with two private collections of gioielli d’artista, thanks to Gregorietti’s publications I had the opportunity to encounter another way to conceive of art jewelry. Although recent publications such as Gioielli d’Artista in Italia 1945-1995 completely disregard the activity of art jewelers, following Gregorietti I traveled to Padua. There I found not only the school, but a link to the international art jewelry scene. At the university, the reality of art jewelry, its history and protagonists, was just not found in the program. In Padua, thanks to the activity of the Municipality, of two private galleries and the library of Istituto Pietro Selvatico, I started researching and developing a series of reflections that I’m still carrying forward.

In the past fourteen years something has slowly begun to change in Italy. We have more galleries and spaces that show art jewelry. But in general there is not a real understanding of the value of this kind of jewelry practice. It is still not uncommon to find approaches to this world that reveal old prejudices. In one of the rare articles about this issue in a national newspaper, the choice of language is interesting. Presenting the work of Annamaria Zanella, the articles describes her as a ‘sculptor-goldsmith’ and her work as a ‘necklace – sculpture.’ (Pini 43) Is this just conventional language to make the message clearer to a wide public, or could it be considered the trace of an ancient division between the arts?