This keynote address was delivered on July 5, 2014, at the Auckland Museum, during the Talkfest organized by Objectspace with the support of Creative New Zealand. The program began the day before, with a PechaKucha evening, and continued throughout the day with contributions by makers Pauline Bern, Warwick Freeman, Richard Orjis, and Lauren Winston; curators Finn McCahon-Jones, Henry Davidson, and Moyra Elliott; Professor Linda Tyler; and finally Te Uru director Andrew Clifford. The Talkfest capped my intense two-week trip up and down the North and South Island. It also coincided with a “strong moment” for New Zealand jewelry: the mythical Bone Stone Shell exhibition of 1988 was being reenacted—in a much expanded version—in the pristine galleries of Te Papa, the national museum located in Wellington. Bone Stone Shell: 25 Years On explored the legacy of the original version with more recent work from contemporary makers, under the über-competent stewardship of curator Justine Olsen. Meanwhile, at The Dowse, Warwick Freeman’s and Karl Fritsch’s Wunderruma project—first shown in Munich in March 2014—had just reopened to a fanfare of excitement and debate. The implicit dialogue between these two exercises in self-presentation created an intellectual bonfire that was further fueled by pioneering studio jeweler Kobi Bosshard’s retrospective exhibition at the National, and Areta Wilkinson’s much awaited PhD presentation at the Tutehuarewa Marae at Koukourarata Port Levy. So June had been an exciting period, and the audience gathered in Auckland was everything one could hope for: engaged, diverse, feisty.

The lecture was moderated by Dr. Damian Skinner, whose notes are reproduced at the end. As usual, AJF’s previous editor is nothing if not critical, and my original text was shortened and modified slightly to reflect his comments.

Benjamin Lignel, editor

Although difference and repetition is an old hobby horse of mine, I started to write on the subject in earnest at the invitation of Philip Clarke, the director of Objectspace, who commissioned me to write about the work of Manon van Kouswijk. This paper led to some conversations with friends, and those conversations led to an exhibition that opened in Bergen in April 2014 and in Paris in June of the same year. Between then and now, I thought I had found in the writings of sociologist Nathalie Heinich some neat conceptual tools to define contemporary craft.

According to her, the operating mode of the artist was characterized—at least in the 20th century—by what we could call “disruptive invention”: artistic gestures that are called artistic precisely because they propose something that changes the rules of the game. In contrast, the practice of traditional crafters is often determined by their relationship to both the repetitive and the generic. This concerns the training crafters receive (anchored in improving one’s skills through repetition), and the way those skills translate into production ranges (limited to a few generic forms, and among these forms, to several workshop variants).

In looking at the work of Manon van Kouswijk, I found that her practice, and, by implication, the practice of a number of her peers, was neither simply singular, nor merely repetitive. Taking my cue from Heinich, who made much of the opposition between the sociologist’s quest for universal truths and her befuddlement when faced with the irreducible singularity of art, I thought that the tension between the singular and the generic was, very possibly, a defining characteristic of contemporary craft. The purpose of this lecture is to take you on that particular journey, and see what we have in the end.

From Artisan to Painter, from Painter to Artist

In order to arrive at the figure of the modern artist, we need to examine two previous incarnations of the picture maker (this presentation in three acts follows Nathalie Heinich’s study, Du Peintre à l’Artiste, Artisans et Académiciens à l’âge Classique, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1993)

The first one is the artisan or craftsman: working from a workshop, he (and it’s always a he) is in the handed-down business of producing or, more often than not, reproducing images to commission within a fairly narrow iconographic range and a slow-paced stylistic evolution. His time is medieval, his ecosystem is corporatist. He operates and perpetuates himself within an essentially domestic structure, in which fathers train their sons, handing down their name, their tools, and their skills. (However, Heinich reports, one could also short-circuit the system and appropriate the skills of another man by marrying his widow.)

The next incarnation of the picture-maker is the academic painter. He appears in Italy in the 16th century, in France in the late 17th. This early academician claims the liberal arts as his source of competence. His skills were learned in rented rooms, where professors transmitted to a group of students the theoretical ropes of figure- and still-life drawing, rather than in the workshop—which is to say that the academic painter was taught, rather than trained—and he owed his different status to an emphasis on book-based knowledge rather than easel practice.

This new emphasis on abstract learning, born of a desire to emancipate picture-making from the corporatist clutch of the guilds and the apprenticeship format that goes with it, goes hand in hand with the social elevation of the arts: because it relies less on practical knowledge, picture-making starts to attract people not endogenous to the craft world (I’d like to point out that this phenomenon, which takes place between 1680 and 1750 in painting, provides interesting similarities with the progressive liberalization of jewelry teaching from the 1970s onward. Jewelers coming from a jewelry family are the exception now, but they were not a century ago. Most contemporary jewelers are taught in schools, using books such as Oppi Untracht’s Jewelry: Concepts and Technology or Damian Skinner’s Contemporary Jewelry in Perspective).

Liberalization also represents a shift in “who decides”: while the artisan is dependent on the goodwill and appreciation of his client, academies tend to wrestle criteria of excellence away from the client and put it in the hands of specialists.

Academies underplay practical training in favor of an education that is both theoretical and standardized. This standardization, on the one hand, and the newfound efficiency of collective transmission, on the other, have the unfortunate consequence of turning out generations of painters by numbers who reproduce the canon taught in art schools. It is against this figure of the professional painter that rises the third, long-awaited, figure of the artist.

Born in reaction to the rigidity of the academic painter, the artist is represented in 18th century literature and culture at large on the model of the vocational genius of the Renaissance. He—or she—has gifts, and artistic development has more to do with maximizing those gifts than with honing them by repeated practice (as with the artisan) or theoretical learning (like the painter). He or she is predisposed or inspired, and creative genius can come in a flash. The archetype of the precocious genius is modeled on Raphael, and his 18th century incarnation is Mozart.

The criteria according to which the artist’s work is judged slowly individualized themselves during the 18th century. As the public got used to, and embraced, the notions of innovation and originality, so did the criteria for judging a work get gradually handed over to the artist herself. This is her world, her inspiration, her rules. (It is also at this fateful moment that art opens itself to the possibility of being hard to “get,” the province of a select few, and that the work of the critic becomes one of an adventurer trying to excavate in the biography of artists the “reasons” that may explain their mad genius). To conclude my summary of Heinich, let me quote from another text she wrote on the establishment of an artistic élite, where she uses van Gogh as the archetypal end product of this slow transformation:

The figure of Van Gogh provides a paradigmatic illustration of the change over to the regimen of singularity, that favors the unconventional, innovation, originality, individuality, in this new ethic of the avant-garde that will become the benchmark of artistic excellence: Thanks to this, the isolated genius is prized over the crowd and the community of peers, eccentricity over following canons, innovation over the reproduction of models […] The artist is not anymore only he who can be singular, but he who must be singular out of principle, as singularity is henceforth part of his normal definition.

—Nathalie Heinich, l’Élite Artiste, Excellence et Singularité en Régime Démocratique, 2005 (p.12)

- That the work is intentional (visual artists do not use the word “experimental” nearly as much as crafters do, nor do they to set themselves up for the possibility that something may not work quite as much as crafters do.)

- That it is a unique expression of a unique individual

- That the means to create that work are embodied (and circumscribed to) one person, and

- That the criteria for judging a work are negotiable, inasmuch as expertise is shared between three distinct bodies: institutional caretakers, trained experts, and the artists themselves. The larger public, in today’s scenario, does not have much of a say.

While this figure is partly based on actual reality, Heinich is interested by the fact that lone examples have “hardened” into widespread assumptions or expectation. In effect, while the experience of artistic practice has changed dramatically in the last 60 years, the model that emerged in the 19th century and was rebooted by the avant-gardes of the 20th century continues to be a fallback template in our collective imagination. Its resilience to new creative strategies (collective, anonymous, unintentional) is buoyed by several “qualities” that we have a hard time dissociating from art-making and art-loving: originality, total commitment (or dedication to or sacrifice for one’s art), marginality, a cult of authorship, the pursuit of the next style or creative act. It is against this representation of the modern artist that I situate my investigation of the contemporary crafter.

Portrait of the Craftswoman as an Artist: Using the Generic to Singular Ends

1. Manon

Here is how I described Manon’s work in The Generic and the Singular: Portrait of the artist as a Maker (Objectspace, 2012):

In contrast to the bold, iconic statements that we have come to expect from artists, Manon van Kouswijk’s work is subtle, self-similar, and slow going. On the upside—if one wants to stick to artistic clichés—it certainly is obsessive. She has spent 10 years working solely on the bead necklace.

The work that best illustrates the overlap of these two types of gestures (the repetitive and the disruptive) is Perles d’Artistes, a series of “necklaces made on the basis of a strict method; the beads of no.1 are made with two fingertips, no.2 with four fingertips, no.3 with six, no.4 with eight and no.5 with ten. First exhibited in 2009, the objects offer up to scrutiny little else than just that: a series of white (and then coloured) strung beads sporting a growing number of facets, arranged on the page (and in the gallery) as one would geometric models, from the simplest (a large lentil) to the more complex (an irregular decahedron).

There are several things at play in this redundant operation. It shifts our attention away from the object as commodity, onto the performative act of making. This is about listing the tools of one’s trade, and drawing, one set of fingers at a time, a negative portrait of the maker’s hand. The result is a conflicted statement of authorship. At once disembodied (any child could have done this) and very embodied (this is, after all, the ultimate hand-made piece, all fingerprints and signatures), it combines, in a mix that I find slightly explosive, conflicting qualities or ‘traits’ of art and craft: singular and generic, authorial and derivative, spectacular and predictable.”

While the repetitive and the generic are not the same thing, van Kouswijk’s practice demonstrates how they can feed off one another: a generic form (the bead necklace) is re-interpreted through repetitive gestures to produce a series of variants. These, in turn, are reproduced to feed international demand for the maker’s work: she has made several “sets” of five that are difficult to tell apart. So while we can assume that each handmade necklace in the series will bear the mark of its maker—and is therefore unique—it is unique in a way that is conceptually interesting but visually insignificant. In terms of artistic “coup,” it operates in a similar way to On Kawara’s date paintings: executed according to a specific protocol, the necklaces never vary stylistically but are by definition unique markers of a day that can never be repeated.

2. Penelope

In the introduction to the Difference and Repetition exhibition, I evoke Penelope, Odysseus’s wife, as the literary archetype for the “repetitive maker”: again and again she sits down at her loom to weave today what she will unravel tonight. The seemingly endless repetition of the same is strategic: she means to postpone the moment when she will have to choose a suitor, giving her absentee husband some time to kill all those unicorns or cyclops and come back to her. She is, literally, wasting her time and theirs.

She serves as a blueprint for later spinners, those anonymous women holed up in windy castles doing tapestry work while their husbands are off killing boars or crusading. She is also, indirectly, the model for the anonymous producer of folk craft. No one gets killed in this case, but some of the tropes remain: repetitive gestures, an artistic repertoire that is stuck on “vernacular,” and the complex proposition that this vaguely punitive craft activity will produce atemporal artefacts that others will enjoy.

Like van Kouswijk, the three following crafters claim the underdog figure of the craft laborer as a model. Simple gestures flaunting their handicraft ancestry are deployed to revisit archetypal forms that we know: the necklace, the blouse, the handbag. These artists are all, to varying degrees, killing time in laborious ways and making their work the unassuming record of this activity.

All four crafters also claim the figure of the subversive artist as a model. Gestures and forms with specific connotations (of the handiwork of women, of the Third-World tourism industry, or of art therapy) are reenacted rather than emulated: this is a (serious) role they play, in order to pry these forms, these gestures, from their destiny as anonymous things.

3. Monika Brugger, Alexandra Hopp, and Kerianne Quick

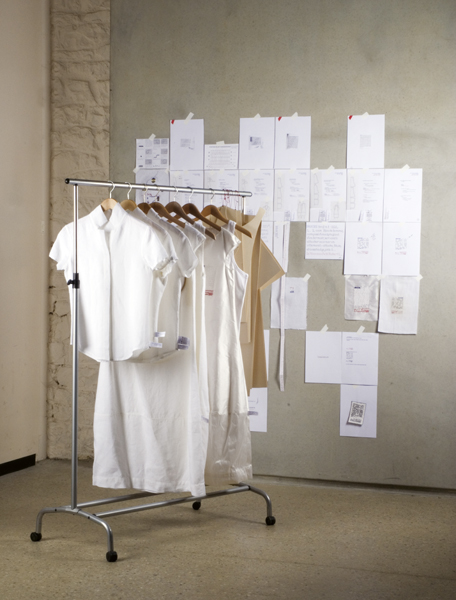

Monika Brugger in Le(s) Petit(s) Robert or The Jeweller’s Studio specifically engages with medieval feminine handiwork: she copies the dictionary definition of the word broche (brooch), using traditional embroidery techniques, onto a garment she has also made. As the definition evolves over time (her collection of definitions starts in 1967 and ends in 2009), so do the shapes of the garments and, more importantly, the technique for reproducing the definitions: from traditional cross stitching (1967) to machine embroidery (2007) and finally transfer (2009).

Brugger purposefully weaves process and time back into Joseph Kosuth’s conceptual proposition (a chair, a photo of a chair, a definition of a chair) by turning the definition into a physical object, and making a show of the tools of her trade. Unlike Kosuth, she is not substituting definitions to the hand-made original, but letting evolving definitions dictate the production of things handmade.

She is the amateur gone nuts, letting her compulsive disorder bore holes through her library of books, from which she culls the weightless silt of millions of words. The meticulous gesture involved in the piece—and its title—point to (and possibly facilitate) a form of therapy, and subsume (jokingly?) the craftsperson’s repetitive actions to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Repetition, for her, is both a symptom of an illness and a cure for it: like van Kouswijk, she is turning repetition into something highly personal.

Kerianne Quick likes to pay attention to certain materials’ capacity to resonate with the history of their place of origin. Leather, once an active element in the Mexican farming culture and transport industry, has devolved from tool to souvenir, she writes: it now tracks, via mass-produced hand-tooled handbags and belt buckles, the mythical origin of the Mexican nation, the pop culture of the North, or the Mexican people’s self-stereotypes. With her Souvenir from the Border series, Quick is interested in corroding this iconography with injections of images from contemporary realities: of these female factory workers building Toshiba TV sets near Ciudad Juarez, of those young prostitutes waiting in neat rows for clients in Tijuana. She uses a combination of traditional hand tooling and new technology, and, in this case, American leather processed in Mexico and sold to American hobbyists and craftspeople in do-it-yourself kits. Her strategy is to pit the conflicting temporalities of vernacular imagery and modern-day newsfeed, to reflect on the modes of production and consumption of these generic products and the images they carry.

Conclusion

In the four cases presented here, customary or repetitive gestures are diverted from their destination as anonymous, vernacular, or therapeutic products. The result is domestic, non-heroic, stealthy. These objects insistently call attention to the process of making, but their success as works is not dependent on skillfulness or, in fact, a posture of de-skilling (i.e. either a presence or absence of skill). Instead, process (minimal, repetitive gestures) is a thematic apparatus that allows this contemporary craft to dialogue with (and revisit) a long history of anonymous craft.

This lecture was about looking at the comparative values of the singular and the generic, of the unique and the serial. Since the singular is generally considered “best,” it may sound like an apology for repetition.

It is not. I am interested in objects that have a slightly less-than-perfect track record as artworks: objects that flirt with their own cloned version. One of the reasons I find them exciting, I suppose, is that they call attention to the laborious project of making things in a way that is conceptually fruitful, while putting craft’s dependence on a relatively narrow repertoire of forms at the centre of their investigation. At the end of the day, the supposed antagonism between “newness” and strategies of repetition is built on antiquated representations of what an artist can or should be: craft-based creative practices can probably benefit from thinking about the economy of production and distribution they belong to, and either mine their allegiance to the repetitive, or make a good case for being unique.

Response to Benjamin Lignel’s Talk, Difference and Repetition

Damian Skinner

In Benjamin Lignel’s talk, the disruptive craftsperson is self-reflexive about the characteristics of craft: repetitive gestures, vernacular forms, atemporal artifacts. He or she stages these qualities through objects and practices, and in staging them, in being self-conscious about them, is no longer bound to them or subject to them. The work is not just an example of craft but instead becomes about craft. It is a representation of craft, aligning these practices with a contemporary art interest in craft—which tends to be an appropriation of the signs of craft. Lignel says “Process . . . is a thematic apparatus that allows this contemporary craft to dialogue with (and revisit) a long history of anonymous craft.”

There are, I think, a number of questions that we should ask about this talk. How efficacious is Lignel’s analysis? Does it allow us to think differently about craft and craft issues? Does this talk account for the current state of things (an important and urgent task), or does it offer prognosis and action to change the state of affairs in which craft finds itself? When Lignel begins with art, and the history of artistic practice, does he just re-inscribe the provincial relationship that craft has to art? But given craft’s historical (since the late 1960s) love affair with art, how do you talk about the core of craft—the disruptive craftsperson—without also talking about art?

What would happen if Lignel didn’t end his analysis with the flourishing of the modernist genius, but instead pursued this topic to more contemporary thinking about the failure of modernism? Originality, as Rosalind Krauss and others have noted, is the consistent theme of all modernist movements, and yet look at the grid, for example, which subsequent generations of avant-garde artists have claimed in their pursuit of innovation. As Krauss correctly notes, no one can claim to have invented the grid, and the grid itself is resistant to invention and leads only to repetition. And so both art history and art practice have exploited the secret of modernism that is hidden in plain sight: that repetition guarantees the original and the authentic. The multiple is, in fact, the condition that is necessary to make the real, the first, the true even possible.

- Difference and repetition

- Invention and repetition

- Singular and multiple

- Original and copy

- Unique and generic

Authority sits differently in these terms. Some are pejorative and others are not. We should consider whether these are equivalent, and if they are not, how their use changes the intentions and possibilities of Lignel’s talk.

Is process the same as repetition? Where does process fit into the binary that Lignel takes as his subject? I’m conscious of a fair amount of slippage in this talk: for example, the move from generic actions or forms in craft, to the idea of generic commodities produced by the flows of global capital. Are they both generic in the same way, or in a way that can be held as equivalent?

What about our obligations to vernacular craft? Or, better yet, our relationship rather than our responsibilities. Lignel speaks from the center of contemporary craft, as pretty much all of us do. But what would happen if we moved from that position? Would we discover alternative ways to talk about, and theorize, the vernacular?

Finally, in a talk called Difference and Repetition, it seems to me that difference is the term that creates the biggest instability around Lignel’s subject. This is not really to do with Lignel’s approach to the subject, but his decision to give this talk in Aotearoa, New Zealand, where the dynamics of settler colonialism play havoc with concepts imported from elsewhere.

Let me propose something: craft in Aotearoa is Pākehā customary art. Like customary art of Māori and Pacific peoples, it is a practice with a difficult relationship to modernity, is strongly governed by conventions (of practice, models of education, materials), is oriented to, or extremely conscious of, the past, and feels under siege by modernism and contemporary art.

The idea of a relationship between craft and customary practice leads us to entirely different, indigenous systems for thinking about the binaries in Lignel’s talk. Taonga (Māori objects that have ancestral value) elude the capture of the theoretical system that Lignel describes, and escape the binary of invention and repetition, singular and multiple, unique and generic. That’s why I thought it might be a good idea to stage our discussion of Lignel’s talk under the protection of Hine-Ahua, a hei tiki by Areta Wilkinson. She is a copy and a multiple, and yet is singular, an individual with a name and a mauri, a spirit.