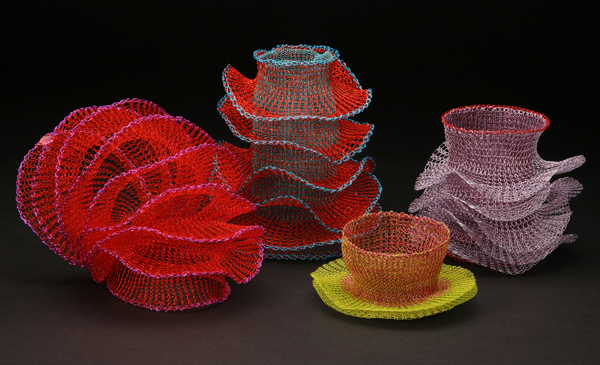

Arline Fisch is an American jewelry pioneer. She is also one of the earliest American post-war jewelers to be shown and collected in and outside of the US. Starting the San Diego State University metalsmithing program and teaching there for more than 40 years, she has influenced hundreds of jewelers who studied under her. Still going strong and still curious enough to join AJF on our trip to Amsterdam last year, she is a true example of the strong spirit of the post-war generation. This show at Mobilia Gallery called Hanging Gardens features the colorful new work by Arline.

Arline Fisch is an American jewelry pioneer. She is also one of the earliest American post-war jewelers to be shown and collected in and outside of the US. Starting the San Diego State University metalsmithing program and teaching there for more than 40 years, she has influenced hundreds of jewelers who studied under her. Still going strong and still curious enough to join AJF on our trip to Amsterdam last year, she is a true example of the strong spirit of the post-war generation. This show at Mobilia Gallery called Hanging Gardens features the colorful new work by Arline.

Susan Cummins: You are one of the reigning queens of jewelry making now, but you had to start somewhere. Could you tell the story of how you chose to make jewelry?

Arline Fisch: Becoming an artist was my goal from an early age. I chose Skidmore College for my undergraduate study because it had a large studio art program within a liberal arts curriculum. I enjoyed combining studies in literature, language, and psychology with studio work in painting, crafts, and design, receiving a degree in art and art education. Curiously, I did not take any jewelry courses.

My interest in teaching at the college level led to immediate enrollment in a masters degree program at the University of Illinois in Urbana/Champaign. As part of my course requirements, I took painting, ceramics, and metal in my first semester, and I found that working in metal was the most satisfactory. The professor in the metals area was Arthur Pulos, a well-known silversmith whose curriculum included design and techniques in both jewelry and smithing. I continued to work in metal for the entire two years of my MA program, although I was not sure where it would lead me.

My first teaching position was at Wheaton College in Massachusetts, where I taught studio art (drawing, painting, printmaking) to art history majors. I needed to find a studio for myself, and I discovered that the area (Taunton, Attleboro) was a center for jewelry manufacturing, and that there were many skilled craftsmen who worked in a factory during the day but had private studios for their own work. One offered to rent me bench space, where I could develop my own designs and acquire additional technical skills.

After two years on my own, I felt the need for more technical training, so I applied for and was awarded a Fulbright grant to Denmark, where I was enrolled in the goldsmiths’ program at Kunsthaandvaerkerskole. My fellow students were highly technically skilled since they had already completed a five-year apprenticeship, but they were in need of design instruction, so drawing and design assignments comprised most of the course with only one day of actual making. This was not what I needed. After a few months, I was able to arrange to work in a large jewelry workshop where I presented my designs to the workshop leader for his approval and was given assistance as needed. It was a great opportunity, and I was able to complete several silver bracelets, brooches, and a necklace, each of which involved a different construction technique.

After two years on my own, I felt the need for more technical training, so I applied for and was awarded a Fulbright grant to Denmark, where I was enrolled in the goldsmiths’ program at Kunsthaandvaerkerskole. My fellow students were highly technically skilled since they had already completed a five-year apprenticeship, but they were in need of design instruction, so drawing and design assignments comprised most of the course with only one day of actual making. This was not what I needed. After a few months, I was able to arrange to work in a large jewelry workshop where I presented my designs to the workshop leader for his approval and was given assistance as needed. It was a great opportunity, and I was able to complete several silver bracelets, brooches, and a necklace, each of which involved a different construction technique.

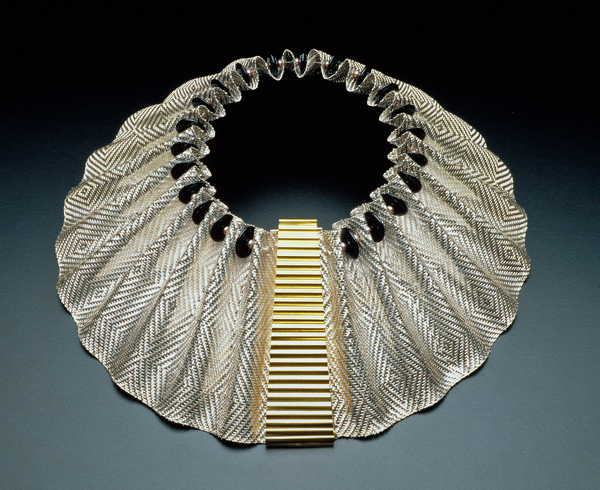

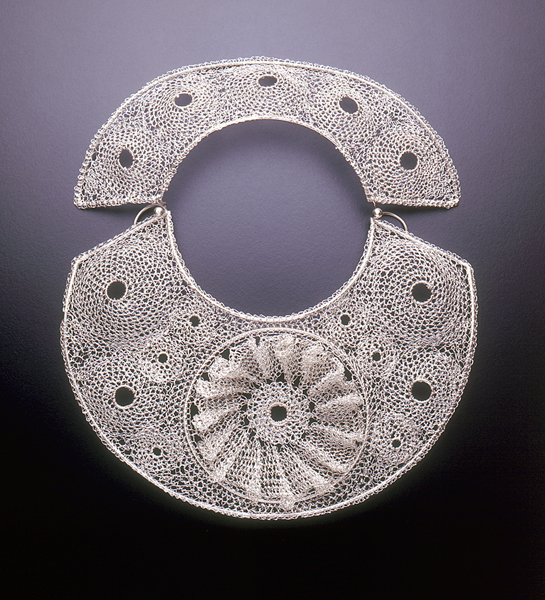

After Denmark, I was more interested than ever in the design and making of jewelry. I was never really interested in making rings or earrings—I wanted a larger format with more dramatic possibilities. I had spent a great deal of time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in their Egyptian collection and was fascinated by the large broad collars, the headpieces, and the diadems of this ancient jewelry. I admired the simplicity with which it was made as well as its dramatic impact. I wanted to make spectacular jewelry that could be at home in the twentieth century. I discovered artist-made jewelry in New York galleries—Sam Kramer, Art Smith, Ed Weiner—that was intriguing in materials and scale, and most importantly Alexander Calder, whose immediacy of working almost solely with a hammer was very inspiring.

I was offered the opportunity to take on the weaving program at Skidmore College since there was no chance for me to teach jewelry (Earl Pardon was already well established in that area). It was a totally different experience to work in soft materials and strong color. It proved to be a fruitful contrast, which remained separate from the jewelry I was making until a trip to Peru opened my mind to the possibilities of combining the two technologies.

Several exploratory pieces combining metal and fabric or metal and yarn followed for several years until, finally, I began to use weaving and knitting directly in metal. Experiments with a wide variety of textile techniques continued over many years, leading to collections of work in woven gold, braided silver, loom woven patterns in silver, machine knitted collars and bracelets, crocheted lace and ruffles, and most recently, installations of multiple sea forms and hanging flowers.

You started the San Diego State University metalsmithing department in 1961, and a few years ago you retired. What did you find most satisfying about teaching all those years?

You started the San Diego State University metalsmithing department in 1961, and a few years ago you retired. What did you find most satisfying about teaching all those years?

Arline Fisch: Developing the jewelry and metalsmithing program at San Diego State University was challenging and exciting. Planning a curriculum for students from beginner to masters’ degree was constantly engaging, as was providing design and technical assignments and projects. I learned so much over the years as new materials and processes became available for studio artists. Providing instruction in traditional techniques and linking them to a history of the field through lectures and readings was an equally satisfying component. I felt reinvigorated as every new semester began, eager to introduce new ideas and to advance the technical skills of the students. Interim and final critiques were always enlightening, as accomplished and often-adventurous work appeared for discussion. I think it is that kind of interaction and stimulation that was the most satisfying and which I miss the most in retirement.

Over the years, many jewelry friends from abroad came to visit, sometimes for a few days, sometimes for several weeks. They were always willing to meet with students, giving formal lectures, sharing their work, teaching a process, and bringing new information and insights from other parts of the world. I was delighted to share my international experiences and friendships, which helped to expand students’ vision of and possibilities for contemporary jewelry.

Can you share a favorite story of a student or assignment that was particularly memorable?

Can you share a favorite story of a student or assignment that was particularly memorable?

Arline Fisch: Spectacles. Making a pair of eyeglasses was a one-time assignment for graduate students. It began with “sunshades” made of paper to develop a sense of scale without involving a lot of engineering. This was followed by the task of making an actual pair of spectacles in metal. A visiting student from Denmark made reading glasses in anodized aluminum in turquoise and purple that were so stunning and beautifully made that I wanted to buy them. She refused my offer, saying that they were a prototype for commercial production, a somewhat unrealistic ambition. Another student made a very minimal design in gold wire with elegantly engineered hinges, but the general consensus of the class was not great enthusiasm for the project. Several months later, the anodized aluminum reading glasses were indeed in production, and I was able to purchase a pair. Five years later, the other student called to say that she was now designing eyewear for several well-known fashion houses, a totally unexpected outcome since she had not really enjoyed the original assignment but was now happily engaged in using what she had learned.

You have shown and traveled all over the world since the 1960s. Could you reflect on how the contemporary metalsmithing world has changed in the past 40 years?

You have shown and traveled all over the world since the 1960s. Could you reflect on how the contemporary metalsmithing world has changed in the past 40 years?

Arline Fisch: Since the 1960s, contemporary jewelry and metalsmithing has changed from a European and tradition-centered field to a global one. In Denmark in the late 50s, my proposal to make salad servers in sterling silver with brass handles was a scandal, yet their silver tableware was acclaimed worldwide for its elegant simplicity and fluid form. Most of this work was designed by architects.

In 1972, I lectured throughout Australia on American jewelry and metalwork, including such people as Fred Woell, Bob Ebendorf, and Marjorie Schick as examples of a more experimental design approach. The response was a bit guarded but interested. The same was true when I lectured throughout England and Scotland in the 1960s, however the mindset was certainly changing as exhibitions and publications became more international. European jewelers were experimenting with new forms and expanding their materials beyond the traditional. In the late 70s, an exciting shop called Cheap Jewellery opened in London, showing a vast expanse of nontraditional work in fabric, wood, plastic, anodized aluminum, and found objects. In Europe, there appeared serious and elegant work in steel, glass, and plastics. Suddenly, it seemed, jewelry around the world had entered a new era, which has continued to evolve in ever more interesting and experimental directions.

Can you describe some of the most exciting pieces of jewelry you have seen in the past year?

Arline Fisch: At Taboo Studio in San Diego, there is currently an exhibition of the work of Brooke Mark-Swanson, whose necklaces I find most intriguing. She works with a landscape theme and assembles unusual fragments of materials to create seemingly casual compositions that suggest place and mood. I especially like Black Vista and Between Forms, whose diverse materials are both sensuous and mysterious and whose neck chains are inventive and effective.

Another gallery artist whose work speaks to me is Myung Urso, who creates delicate forms by stitching silk and cotton fabric to minimal wire constructions. Some pieces are like three-dimensional drawings with a sense of spontaneity. Others use a singular strong color that adds a touch of playfulness.

Another gallery artist whose work speaks to me is Myung Urso, who creates delicate forms by stitching silk and cotton fabric to minimal wire constructions. Some pieces are like three-dimensional drawings with a sense of spontaneity. Others use a singular strong color that adds a touch of playfulness.

Of the artists visited on the recent AJF trip to Amsterdam, I was most impressed by Beppe Kessler, whose range of work over many years reflected her interests and experience as a painter, especially in the delicate but complex use of color.

What have you seen or read in the past year that you can recommend?

Arline Fisch: Books I have read and recommend are: Contemporary Jewellers, Interviews with European Artists by Roberta Bernabel; Calder Jewelry published by the Calder Foundation, the Norton Museum of Art, and Yale University Press; and David Watkins/Wendy Ramshaw, A Life’s Partnership by Graham Hughes.

What are you looking forward to doing in the next few years?

Arline Fisch: In the next few years, I will continue to work quietly in my studio on a project called Angels and Saints, a series of silver pendants commemorating female saints accompanied by several angels. This has been a long-term endeavor with a goal of 26 saints, one for each letter of the alphabet. Thus far, there are 14 saints and two angels, so there is still much to do.

There is also the need to organize materials and images for the Archives of American Art and the archives at San Diego State University, a task I am sharing with a former student.

Thank you.