From January 13–March 29, 2015, the Viennese public has the opportunity to see two rare exhibitions of contemporary jewelry in its city. Both exhibitions take place at MAK under the title Schmuck 1970–2015 and include a retrospective of Fritz Maierhofer’s work of the last 45 years and also an overview of the Heidi and Karl Bollmann collection. Margit Hart has interviewed both Karl Bollmann and Fritz Maierhofer for AJF. This is the first of those interviews.

In the past decades there were only three larger shows in Vienna dedicated to this specific field: Schmuck International 1900–1980 in 1980, Turning Point in 1999, and Kunst Hautnah in 2000. This might be connected to the fact that the university is not offering a jewelry program anymore, and so an academic discourse is missing in Austria.

It will be interesting to see if Schmuck 1970–2015 will have the potential to initiate a revival of the scene as well as a broader acceptance of art jewelry here in Austria.

Margit Hart: Mr. Bollmann, it’s the first time that you have shown your collection to the public—why now?

Karl Bollmann: It was decided on very short notice that the exhibition would take place now, and so it has come about under great pressure. It is mainly my wife’s wish to make “New Jewelry” better known in Austria. We regard the exhibition as a kind of “thank you” that we are dedicating to the artists, so that Austrian museum visitors see what’s happening in this field. The exhibition is proving very successful in achieving this goal and the reactions in the press, too, are positive and excellent—a well-earned performance.

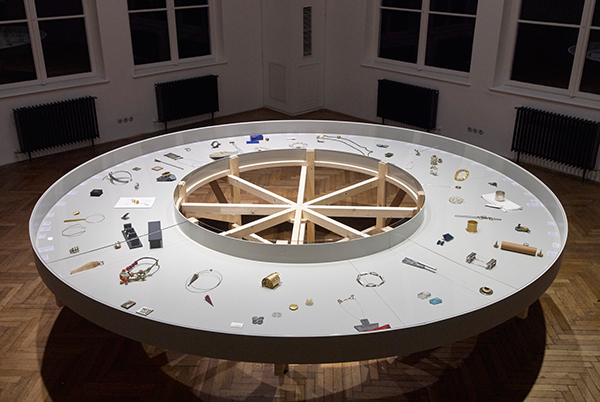

You had to restrict yourself to about half of the pieces you’ve collected. Could you tell us what aspects were important for your choices? The show is divided in three sections—1960 to 1999, “Project 2000,” and 2001 to 2014—yet the exact years when the pieces were made are not indicated. What do you want to convey to the viewer by creating this structure?

Karl Bollmann: We wanted to show the development of New Jewelry and perhaps also to ask whether this development has actually taken place. The original idea was to show a maximum of two pieces of jewelry by each artist—one from before the turn of the millennium and one from after, with the “Project 2000” in between. To me, that would have looked like the works were a bit “lost,” so Heidi decided to arrange them in groups covering 10-year periods. As far as the position of each piece in the exhibit was concerned, aesthetic principles were used, though, and this was perfectly right. We didn’t actually intend any particular artist to be highlighted, but if we’d used our original idea, people would only have seen the diversity but would not have been able to focus on anything. That’s why there are also eight individual sections devoted to Hiramatsu, Sajet, Martinazzi, Zanella, Skubic, Kodré, Nisslmüller, and Bischoff.

As already mentioned, 10-year steps were planned; they also structure the catalog. When a piece of jewelry is strong, it’s not important to state the date when it was crafted. But from a comparable situation and to answer the questions “Are certain aesthetics recognizable?” or “Were the jewelry-makers of the older generation pioneers?” it would have been better to state the precise date.

Contemporary jewelry stands outside of the usual categories, or at least outside of common categories related to jewelry. Yet we all are trying to come up with a label for it. How do you feel about this issue? Would one specific term be helpful?

Karl Bollmann: It makes sense to consider a new name for jewelry as far as new perceptions of it are concerned, and also if one is of the opinion that New Jewelry was revolutionary. It makes sense, too, if you believe that the old name “jewelry” is encumbered by the reproach that it involves pretense, vanity, and self-praise. “New Jewelry” expresses it best for me. If you declare that it is art, the jewelry aspect of it disappears. Art is certainly a further but not a sole criterion.

What was the actual starting point of your collection?

Karl Bollmann: The starting point is described in the Skubic book, Between. I had inherited some diamonds, so I wanted to have a piece of jewelry made from them for my wife. You naturally have a certain idea that should match the period and current artistic appreciation. So I wandered from jeweler to jeweler and had terrible experiences—absolutely impossible! Then I happened to be passing the MAK and popped in to see the Jewelry 72 exhibition. Peter Skubic was also there, introducing himself most amusingly to a school class. At that time, he was showing some very dynamic, powerful jewelry. I approached him about my diamonds and the result is lying here in a glass case in the museum! Peter had also brought the Tendenzen catalogs from Pforzheim along and really explained from the very first day what kinds of changes were about to happen in jewelry.

What is the main impulse for acquiring a piece?

Karl Bollmann: This of course changes, and is very complex. Jewelry first fascinates via its spontaneous impact, and it’s impossible to predict when that’s going to happen. That then perhaps some sharp-witted contemplation appears is certainly nice, but need not be the case.

Did your perspective or your personal focus on what was important to be collecting shift over the years? As you were choosing pieces for this exhibition, did you rethink this?

Karl Bollmann: Surprisingly not! I’ve given some thought to whether the way we look at it or our attitude has changed, but nothing has. It has to function as jewelry. In the 1990s, I began to think over why I reacted in this way and what aesthetics means. But my choice of jewelry and the pleasure I derive from purchasing it have changed relatively little.

We deliberately chose smaller works for this exhibition as there should be evidence of wearability and emotional bonding with the wearer.

That means we go into a museum and exhibit jewelry to introduce people to it and explain to them that the way we look at exhibits in a museum, by which I mean the “glass case view,” achieves nothing for jewelry. You need to try it on outside and put it on your clothes—that’s the point of all this. If someone just finds two pieces that seem passable, then the show fulfilled its purpose.

You and your wife both wear jewelry, which for me makes a big difference. Other collections are stored in boxes or are only shown in museums. When do you wear jewelry? Do you get comments on the pieces?

Karl Bollmann: Of course we vary our jewelry according to the opportunity. That’s generally done this way. Other women’s reactions to my wife’s adornment show surprisingly little or no envy. Basically, they’re not against her wearing this kind of jewelry. When men wear jewelry, women have nothing against it either. They find it amusing and are tolerant. Men, in contrast, are occasionally annoyed.

Can a collector be a role model for other people interested in jewelry? Have you experienced that process?

Karl Bollmann: No. In the past, we expected to encourage people to wear contemporary jewelry themselves simply through the act of collecting, but today I regard that as extremely unlikely. We are more effective when we wear jewelry.

I don’t see myself as a collector. I see myself as a purchaser who enjoys giving jewelry to his wife and who is very pleased when she is wearing it, and who is also pleased when it goes down well in society. Of course this is a role model. But the intention behind the process of collecting lies in the fact that we see superb artistic and human quality in this jewelry, which deserves courage and encouragement.

Recently I visited the symposium Schmuckdenken/Thinking Jewellery in Idar-Oberstein, which had the focal theme “Art between leisure and social responsibility.” Do you think that collectors should be conscious of these two themes?

Karl Bollmann: I’m aware of the issues involved here. The whole exhibition, which at first scares a collector, came about through social responsibility. When buying a piece that’s of no importance—it would be hypocrisy to claim that. I buy a piece with the idea that it means something of lasting value to my wife and myself.

You have a keen interest in philosophy, especially in Kant—can you point out the main aspects of your philosophical approach to jewelry?

Karl Bollmann: Kant describes my problem to the extent that he wonders whether it is permissible at all to suggest one’s own aesthetic judgment to another person. Why may I say that a piece is beautiful? Why not only that I like it? I’m of the opinion that this jewelry possesses universal validity. Kant rejects jewelry as a sign of vanity and says it impairs genuine beauty. Does real beauty exist at all? I do think jewelry can contribute to perfection.

And I really believe it to be a function of our culture, as Kant suggests, to foster a general feeling of participation and also sympathy, as well as the possibility to communicate our thoughts to others. This happens with jewelry naturally and rightly via the wearer’s imagination but also via that of the artist. The two need to be able to, and want to, do this together. The idea is that this refinement of communication should become reality in New Jewelry.

I also want to mention your “Millennium Project” or “Project 2000.” You invited 61 international artists to create a piece of jewelry for your wife, Heidi. Did the finished pieces fulfill your expectations?

Karl Bollmann: I actually had few expectations. I decided to do it but had no objectives. The idea was really sheer curiosity regarding what artists do when they are totally free and know that their work is going to be bought. Some people have also asked to be invited. This exhibit shows the results. My wife and I are very pleased with it.

Do you think people find it more difficult now than they did 40 years ago to form an understanding and an (immediate) emotional response to contemporary jewelry?

Karl Bollmann: It has surprisingly not become easier for jewelry artists. In fact, it has become harder… Why? Because the thinking of intellectuals is focused more toward economics and marketing than it used to be. Today, people think basically only in terms of the market, and if this is instilled into young people more and more, it will become difficult for imagination and its appreciation, as well as the communication of imagination, which is essential.

Thank you.