In her latest body of work, Body Politic, Melissa Cameron departs from earlier themes to explore the political arena. Melissa confronts her fears regarding weapons of war in a series of works imbued with her signature piercing precision. Rich narratives are embedded in oversized jewels and wall works that reward digging deep. Expanded definitions of the body as vehicle for jewelry are revealed, and what is brought front and center is man’s ongoing inhumanity to man.

Vicki Mason: What led you to jewelry as a career after your initial degree in interior architecture in Perth, in Western Australia, and did you undertake any formal training?

Melissa Cameron: In grade 10, in high school, for an assignment I shortlisted two careers: jeweler and architect. Ten years later I was working as an interior architect in Perth and making jewelry for friends and to sell at a local market on the side, knowing that the jewelry I had made in high school was more intensive and satisfying. After a dark night of the soul I had an epiphany (which actually occurred in daylight hours at the Art Gallery of Western Australia; while looking at the Howard Taylor retrospective I realized that people from my town could be artists), and I acknowledged that while I loved architectural design, I loved jewelry too, so I decided to head back to school. I had been accepted to undertake some making units back at my old university under Brenda Ridgewell when I was involved in a car accident at work, which accelerated my transition process somewhat as I was suddenly unable to work full time. I completed a year-long postgraduate diploma of jewelry production at Curtin University, and then my new husband and I packed up and moved to Melbourne so I could undertake a master’s of fine art under Marian Hosking at Monash University, which I completed in 2009.

You moved from Australia to America in 2012. Has this move, and adapting to and living within another culture, affected your work?

Melissa Cameron: Yes. As I said in an artist statement in 2013, “As with all intercontinental moves—even between two English-speaking countries—there are many subtle and not-so-subtle differences between the cultures for the new settler to contend with. This shift, a literal and metaphorical displacement, has altered my way of living so completely and yet so inscrutably. Each individual effect of the transition, while seemingly small, has coalesced into a huge yet unseeable force that has changed my life in so many ways it is hard to even begin to recount them all.”

I can say now that the move really affected my sense of myself as a political body. In many ways my situation makes my political standing feel precarious—but at the same time because of the way that the United States is structured, even though I as a political body have very few rights, as an economic body I am afforded better opportunities than many who were born in this country.

You’ve titled your new exhibition Body Politic, which in the dictionary I looked at is defined as “a people regarded as a political body under an organised government”. Are you also playing with ideas about the human body as political, discussions around sexuality, our own autonomy over our bodies, etc., all of which potentially sit under the umbrella of your title? Which of these reference points were you interested in exploring?

Melissa Cameron: I’ve been looking into Aesop’s fable of The Belly and the Members and other literature that informs the idea of the body politic, and I am stuck on the idea that an organized government is meant to be representative of the people that form its constituent parts (admittedly the class distinctions implied in many a retelling of the narrative stratify more or less specifically who holds the most power.) I personally am beholden to a state that does not represent me, as I am not allowed to vote in the country in which I live. Yet as a white woman of a certain class, my interests are often better represented than those of many citizens of that state, which makes me question what, or rather who, constitutes the state and, inversely, who it is meant to be representing. I find this question especially potent when a state makes decisions that are against the actual human bodies of its members, and the opposite, when you are not a member of said state, what gives that state a claim against your body. The tension that exists between these two ideas—who has the right to make a decision about my body, and what gives them that right—are the ideas that I have been investigating, through the long history of this tension played out in armed conflict.

Where does your interest in weaponry and the tools/machinery used for killing another human being come from?

Melissa Cameron: I think I have the opposite of an interest in weaponry. I have a grave fear of the tools and machines that are used for killing people. I wanted to counter my own fear, and the idea that I think many of us have, that the weapons we have developed today are so much more dangerous, more lethal, than those of previous generations. I have an interest in history and archaeology, so I went in search of weapons from historical cultures that could lay claim to being equally gruesome to the ones that we might encounter today. In one sense my fears are just more grounded now, since the weapons I have depicted mark out the devil I know.

Can you please explain the curious titles of works like, for example, 154 @ 30 rpm (scale 1:4)?

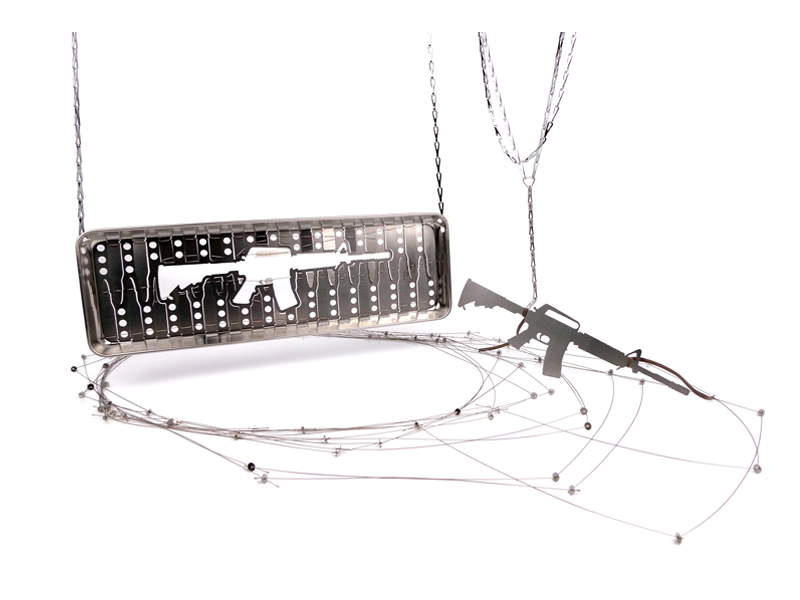

Melissa Cameron: The titles offer a truncated explanation of the works, but are probably more successful in prompting the viewer to ask questions. In most cases they relate to facts and figures that are at the foundation of the pieces, like the number of iterations of a motif or the scale of the artwork in relation to the scale of its referent. Several works are made in such a way that when fully unfurled they are full-scale depictions of what they name; the Arrow 1:1 and Bow 1:1 works can be laid out to show the full length of a period bow and arrow. The M1 Abrams is a type of tank used by many nations, including the Australian Army. The title 1100 Shot Round refers to the amount of holes that were drilled into that work, which itself references a particular cartridge (the M1028) that when fired from the cannon of the M1 Abrams has a shotgun-like effect, in that it sprays out close to 1,100 individual 9.5mm (3/8 inch) tungsten balls. The 154 @ 30 rpm (scale 1:4) from the Gun work, which you refer to in your question, uses a particular incident to illustrate the AR-15’s capabilities. In the incident, it was counted that the weapon was fired 154 times in a between 11- to 14-minute period. It was reported that the shooter frequently reloaded the 30-round magazine before emptying it. In the piece there are 77 confetti-sized holes cut through the steel, and the 77 cut-out pieces are used in the neckpiece, making 154 representations of bullet holes in the whole series. There are 30 shells depicted on the same piece, representing the 30 rounds per magazine that the weapon can hold, and the rifle itself is depicted at quarter scale, which is denoted by the 1:4 in the title.

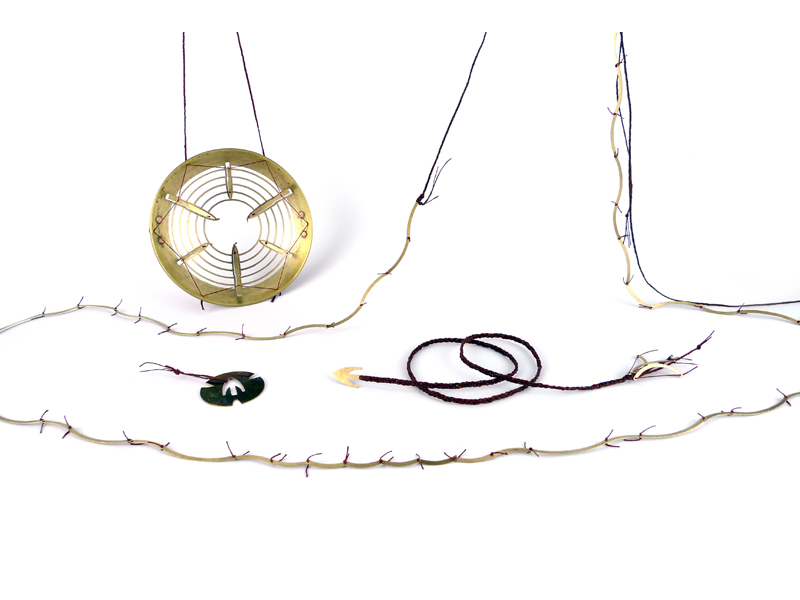

I’m interested in the works from the Escalation series. Your work Tank is made from a non-stick pan and the works RPG@1:9, 22 radius@1:9, Anti-personnel Round, and Un-handle are made from a hand trowel. The strength of this work derives in part from the oxymoronic relationship between domesticity and warfare and the affiliation that you forcefully create between them. There are various ways to argue the interconnectedness of the military with the domestic. Can you talk us through how these everyday objects from the kitchen and garden relate to the tank and machine gun, both weapons for killing?

Melissa Cameron: As you say, there are many connections between weapons and domestic objects. First and foremost, they are both tools used daily by humans, and both were designed, or evolved, alongside the human body.

A striking connection for me comes down to the mutability of material. As an artist who likes working with steel because of its material properties, I know that a piece of steel, when of a certain width and grade, cuts just like another piece of steel. A new flat sheet will cut like a hand trowel, will cut like a tortilla pan. Materially I value its strength and weight, the same as many other designers and manufacturers, and because of that, one piece of steel might end up on my table, or in my garden, and another piece might go to the instrument panel of a tank, or to form a part of an RPG-7, an anti-tank rocket-propelled grenade launcher. With an in-demand commodity, the organization of the market determines where each new piece of steel goes. If there is more money to be made in one arena, chances are more steel will end up serving that area of the market. What makes my domestic steel different from that military steel? Hardening treatment, and geography. Historically, in times of shortage, it was common that one’s trinkets, or at least scrap steel, would be surrendered to make machines of war, making the two the exact same thing.

I also note that it is my privilege to see the interconnectedness in somewhat abstract terms, as I don’t live in an environment where the two frequently come into contact with one another.

The neckpiece Body/Politic has a message encoded in it, in binary code. Similarly, most of the large neckpieces, once worn, will no longer be recognizable as a sword, missile, etc., nor will their connection to domestic utensils be clear. Which begs the question—to what extent is ignorance a necessary part of your audience’s skill set?

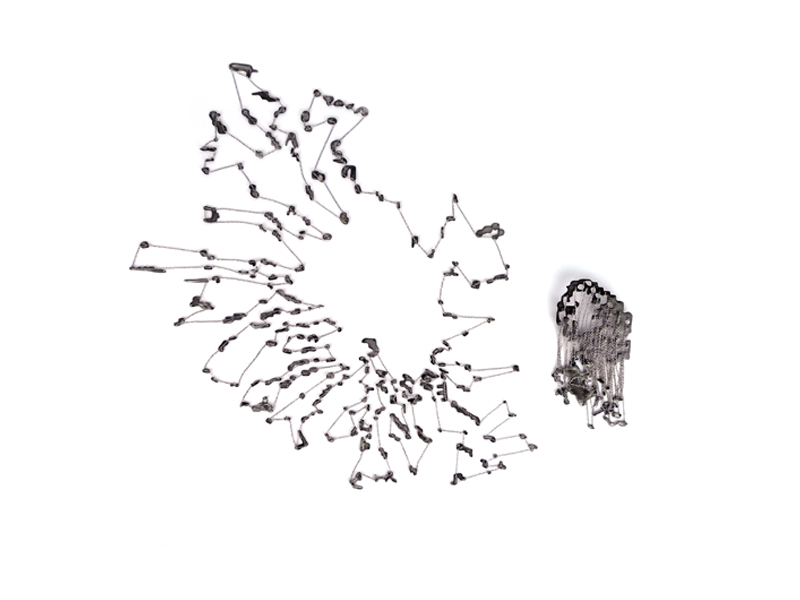

Melissa Cameron: Good question! In this series I became better at obliterating the original object and disguising the forms created from the object as I went along. Some of the earlier pieces are more ostensibly wearable, while in the later ones the functional object has been all but lost. These works are arguably more successful jewelry pieces, as their desirability and wearability is not impeded by their storytelling ability. I would think it hard to wear a quarter-scale rifle and remain ignorant, but in the Drone works the motif is hard enough to make out without decoding the over 1700 bit binary/ASCII message. I think that all jewelry has a narrative, though it is more often one that has been interwoven into the piece by the wearer. To me the strength of jewelry is in this tradition of its holding a meaning and/or message, and so I have encoded my messages in these works, sometimes very deeply. I don’t expect them to be found by most people who see them. But for those who are interested and who seek them out, the reward is hopefully worth the effort, if sometimes horrifying.

In the series HEAT, you’ve made “jewellery for the wall.” What was the inspiration for this?

Melissa Cameron: The jewelry for the wall in HEAT II was the best way to present the story it is depicting. It is my attempt to capture the scale and violence of the force that the original image of the armor-pierced tank documented. Outside of a gallery, the configuration of the long chain will not exist, but on the panels that accompany the neckpiece and the brooch, the story of how they came to take that shape, and how there came to be so many parts, is very clear.

The HEAT panels, like a lot of the work in Body Politic, have an “on” and “off” state. They can be worn, and then returned to the wall, to “complete” that installation. This co-dependency between a sculptural and a wearable object echoes what Seth Papac, for example, has done in his recent series. What do you think is gained or lost in the process?

Melissa Cameron: The HEAT II panels in this installation are not meant to take wearable form, but you are right, in another version I have made one panel a wearable breastplate from the central panel. The neckpiece and brooch are much more easily/traditionally wearable, but are also able to be placed back into the installation configuration.

Obviously the ability for any jewelry work to break down the fourth wall from artwork to personal adornment allows it a freedom to reach out to viewers, a freedom that few other art forms have. In these works, there is at least a temporary trade-off in form and in the work’s easy legibility. These pieces rely on the context of the surrounding works to receive the full message, but I’m not willing to say that a partial interpretation is less valid than the shock of seeing someone wearing a bright red RPG pin on their chest. Being in the world, the works’ potential to communicate anything, and their ability to become the recipients of yet more layered narratives, is enormously increased.

There are many ways to interpret your recent body of work. One of them is that it is a form of commentary on the complicity of every man in every war waged since the dawn of humanity. Are you hoping that people who buy and wear (or exhibit) your work will carry that message into the wider world?

Melissa Cameron: At this stage I’m just happy that you managed to pick up on that message! The reason that I took images of every work displayed on my body is to acknowledge that responsibility for the work, the messages, the motifs, all of it, is on me. I don’t want to assume that someone who owns or wears the work will have that same feeling of ownership of my message. But I also have the feeling that so long as humans deny their role in the escalation of violence we will not see the change needed to end these cycles, so I guess my secret hope is that people will ruminate on my complicity at least.

Having realized this exhibition of new work, will you now go on to expand on ideas it has raised, or is it a discrete series existing as a response to an idea you have now exhausted? In short, what is next on the work agenda for Melissa Cameron?

Melissa Cameron: I’m not yet sure. I had visions of what the Drone pieces would be for over 18 months before I managed to finish them, and I have not had the same attraction to research to the same depth the other weapons that I began investigating in the intervening time. The Caltrops works are little sidelines that I could continue, as in my research I found that there is a couple of thousand years of material to work with, but right now I’m not in a hurry to go there. Investigating this series was really depressing, and as much as there is more that I could find to say, I’m not in a place personally at the moment that I want to extend my own misery in this direction. However, the social and political context that has informed these works has expanded my definition of the body, and the body is what my works serve, so it’s likely that there will be further investigations resulting from that awareness.

The final works I made for this exhibition are the Body/Politic works, which are picking up on these themes at a slightly shifted angle. These ideas are recent and because they are able to deliver short and sharp messages in an appealing format, (and since I don’t have to plumb the depths of what humanity is willing to do to itself in order to make them), I can see myself continuing with them for a while.

What makes a piece of jewelry “pop” and “sing” for you?

Melissa Cameron: The perfect melding of design, intent, and execution. I look for clarity. To me clarity sings.

Do you have a favorite tool and, if so, what is it?

Melissa Cameron: I’m a bit of a tool queen, so that’s a tough one. I can’t go past a nastily pointy pair of tweezers, but I could not work without AutoCad, a drill bit/press, and a decent saw frame loaded with 6/0 blades.

Do you listen to music in the studio/workshop? If so, what to?

Melissa Cameron: I have done, a lot, but in recent times music has become an unwelcome emotional trigger so I tend to listen to podcasts. The Drone works are presented to you by Answer Me This and Radiolab, with help from 99% Invisible and Another Round. Body Politic owes a debt to Snap Judgment and the rest—Escalation and HEAT II—are thanks to a bunch of Australian comedians’ podcasts. As for music, my upset-looking demeanour in the images was helped by Taman Shud by The Drones, Nugget by Cake, and by Future of the Left, PJ Harvey, and Nick Cave, among others.