This essay was first delivered at SOFA NY in April 2012 as an AJF-sponsored talk. The lecture has been modified to meet the format and needs of the AJF website.

Margaret Strong was born in Tacoma, Washington in 1903 and the family soon moved to San Diego. In the 1920s, De Patta studied painting in San Francisco and at New York’s Art Students League. She was particularly excited by European avant-garde art that was shown in museums and exhibitions on both coasts. In the 1930s she turned to jewelry and was already an established jeweler by the time she attended the Chicago Bauhaus in 1940. In the early 1940s, she returned to San Francisco where she spent the rest of her life making one-of-a-kind and production jewelry that was perfectly in line with Bauhaus aesthetics.

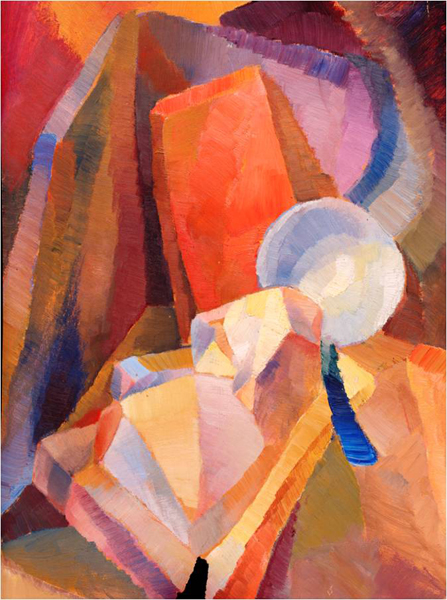

Moholy-Nagy was only eight years her senior, but had been in the forefront of avant-garde art and design in Europe. The two artists shared a compatible aesthetic: abstraction. In early paintings, circa 1921, both artists explored an overlapping series of planes as well as translucency. These paintings were completed decades before the artists met.

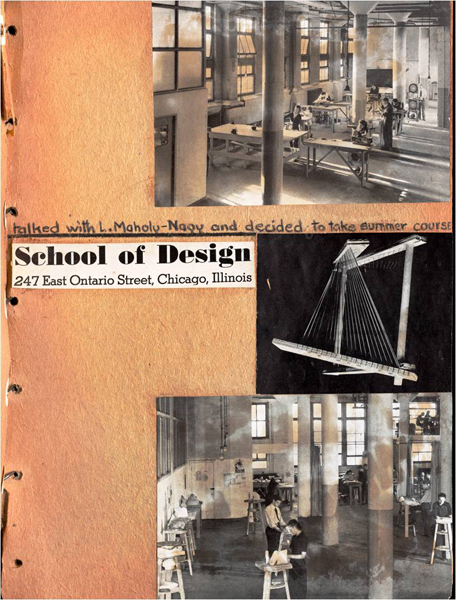

De Patta was sixteen when the German Bauhaus was established in 1919. It moved from Weimar to Dessau and then to Berlin for one final year in 1933 before it closed for good after being raided by the Nazis. As German democracy collapsed in the 1930s, most of the Bauhaus faculty was forced to flee, including Moholy-Nagy, one of the principal Dessau faculty who had resigned in 1928.

It is difficult to describe the Bauhaus in just a few words. It was neither a technical school nor a traditional art academy. The Bauhaus trained artists, designers and craftsmen to create superior design destined for industrial production. Inherent in the Bauhaus philosophy was a democratic principle that good design should be widely available. As a result, students were not trained as specialists but as well-rounded individuals whose talents could be applied to many different design problems. These factors played an important part in shaping De Patta’s life and art.

De Patta’s life took a dramatic turn and her jewelry career was born in 1929 when she was shopping for her wedding ring. When she could not find one with a modernist design, she decided to make her own. This is such a good story – if it were not true, you would have to make it up. Unfortunately, the whereabouts of the ring are unknown. She saw that no one was making jewelry inspired along the lines of modern art. With no formal training programs available, she was primarily self-taught. She turned to books on jewelry making and studied ethnic jewelry in museums. Her very early jewelry experiments demonstrate how she used ethnic museum pieces as models to explore how jewelry was fabricated. A bracelet of beaten metal and simple wire circles and spirals shows a somewhat Moroccan influence. Only a short time later, her work had changed dramatically, becoming carefully balanced, modern compositions. She made pins from flat sheets of silver, cutting out simple shapes that she assembled.

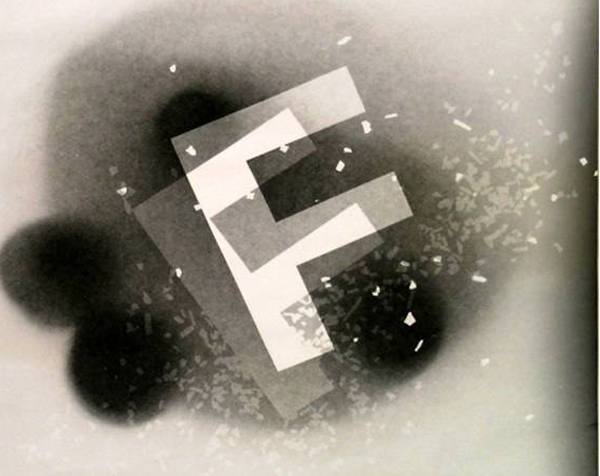

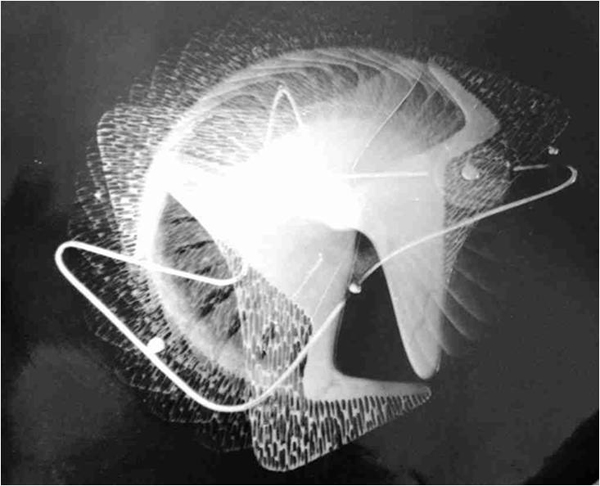

By the mid-1930s, De Patta had stopped painting altogether and before any direct contact with Moholy-Nagy and the Bauhaus, she was already an accomplished jeweler with work that frequently appeared in galleries and in major exhibitions, including the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco. De Patta was increasingly interested in translucency and light and she began experimenting with photography, especially photograms. Photograms were first explored in the 1920s by Man Ray, Rodchenko and Moholy-Nagy, who called himself a light modulator, not a photographer. Photograms are made without a camera by placing objects directly onto photosensitive paper and then exposing it to strong light. The result is a negative image with variations in tone that depend on the transparency of the objects used. The F-shape in one of De Patta’s photograms, for example, might have been opaque cardboard, showing up as white on the paper.

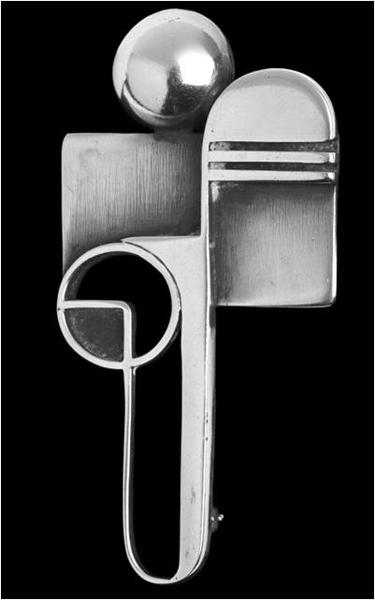

Around 1939, Moholy Nagy gave a Bauhaus lecture in San Francisco in which he showed photograms made by Bauhaus students. After that, De Patta made a great number of photograms herself and often used them as blueprints for her jewelry. A 1955 brooch shows the relationship between the photogram image and the actual jewelry.

De Patta took her explorations of transparency in jewelry to a new level when she began collaborating with Francis Sperisen, a noted lapidary in San Francisco. De Patta would shape and cut wood or acrylic models to show the designs and shapes she wanted and Sperisen would cut the actual stones. De Patta called these stones with complex optical qualities, Opticuts. When Moholy-Nagy first saw her work in 1940, he told De Patta that she was already putting many Bauhaus theories and constructivist ideas into practice because ‘they reflected the same logical working out of structural and spatial problems without using any extraneous elements.’ (Uchida 14)

After the summer course, she enrolled at the Institute of Design in Chicago, which closely followed the principles of the German Bauhaus. The School believed in learning by doing without preconceived notions. All students took the Preliminary Course for the first two semesters of an eight-semester program. De Patta only attended two semesters but those two semesters were a life-changing experience for her. The preliminary course emphasized experimentation and direct experience with materials. But students like De Patta could also participate in the more specialized workshops including, for the first time anywhere, workshops on light, which was one of the most important for De Patta. Surviving paper exercises demonstrate that De Patta was becoming extremely adept at changing a flat surface through cutting and folding into a three-dimensional structure. In an interview shortly after De Patta left Chicago, Moholy-Nagy commented: ‘. . . the best jewelry in the country is made by a former student of ours, Mrs. Margaret De Patta.’ (Engelbrecht 245)

Allowing the wearer to interact with the jewelry, De Patta did not specify a position for her brooches, but left it up to the individual. Components were often movable and colored stones could be flipped to suit the wearer’s mood or outfit. De Patta’s open structure integrated the wearer’s clothing with the piece’s appearance and made the wearer a participant. A kinetic pin now in the MAD collection has three positions to give the wearer a choice of displaying different colors and shapes. There is one component holding coral and malachite stones and another with a textured, bird-like shape that can be placed in a choice of three different positions. Sometimes she would use multiple photographic exposures to capture the kinetic effects of her work.

Over the years, her collaboration with Sperisen intensified and they invented sophisticated Opticuts, including the use of natural inclusions and irregularities in quartz that were generally considered unwanted faults in the crystals. The 1947 ring dramatically exploits tourmaline inclusions to heighten the internal optical effects. The chevron-shaped mounting around the stone forms a counterpoint to the line-like inclusions; De Patta was always concerned that the mountings for the stones would not interfere with the purity of the stone itself. The 1948 pendant, one of De Patta’s most sophisticated and satisfying works, has been referred to as her ‘Cathedral Piece.’ The very fine natural rutile inclusions appear as fine lines, known as Venus hairlines. The thin lines of the setting complement the rutiles and the cantilever suspension of the crystal heightens the effect of the lines within the stone.

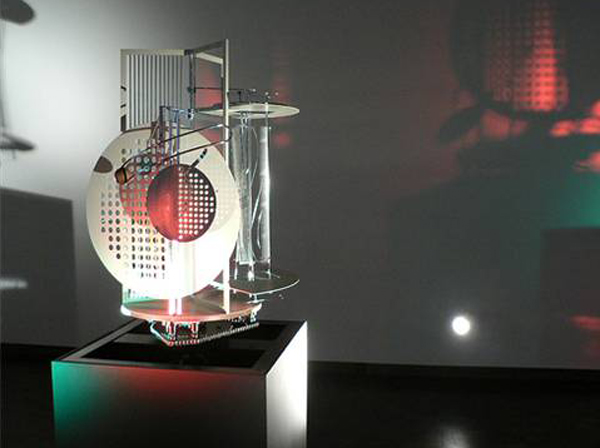

In her 1949 rutilated quartz ring, the facets of the clear stone create dramatic internal reflections and refractions that alter the perception of the internal space and natural rutile inclusions. The combination of internal linear elements bears a striking resemblance to Moholy-Nagy’s Space Light Modulator. The mounting problem was to hold the crystal with a minimum of metal interfering with the play of light and color. As in previous pieces, De Patta cantilevered the metal mounting at the top of the ring to harmonize it with the crystal. In a 1951 pendant, she used a free-form cabochon quartz crystal to visually distort the patterns on the stainless steel screen—the effect recalls some of the screens in the space light modulator. This central element in her 1956 pendant is a beautiful opticut quartz crystal faceted in opposing directions. The double facets distort the straight line of metal behind the crystal, seeming to break up the line, a zigzag effect that De Patta achieved in many of her pieces.

After her year in Chicago, De Patta returned to San Francisco in 1941 and cleaned house, literally and figuratively: she divorced Sam De Patta and replaced an old wooden house on a San Francisco hill with a model of modernist architecture featuring a glass brick corner wall that met the modernist goal of providing transparency and light to the interior.

In 1946, De Patta married Eugene Bielawski, who had been a Chicago Bauhaus faculty member. She had many friends in the Bay Area craft community and was one of the founders of the San Francisco Metal Arts Guild in 1951. She was a devoted teacher and taught at the California Labor School together with her husband. The school strongly promoted democratic principles and was one of the institutions that trained returning veterans, but McCarthy-era politicians targeted the Labor school as a Communist front. The couple was blacklisted and in 1947 they had to leave the school, which closed a few years later. They tried to open their own Bauhaus-type school, and began writing a book on design, but these efforts never came to fruition. Instead, they turned to serial production.

De Patta had become upset that her handcrafted pieces were so time-consuming that she had to charge high prices for them and only the well-to-do could afford them. Selling only to the rich was in conflict with democratic design philosophy of the Bauhaus, which really always had been part of De Patta’s basic nature. The couple decided to design jewelry for the growing middle class and started an important new phase in their lives. In 1946, they founded Designs Contemporary while they were still teaching at the Labor School. With Designs Contemporary, they made production pieces that were intended to be comparable in quality to many of her one-of-a-kind pieces. De Patta designed 40 to 50 master models in silver that Bielawski would cast in limited editions so that the designs would not become too familiar. The production pieces, mostly rings and pins, were sold across the country at affordable prices. De Patta and her husband became packers, shippers and marketers, as well as manufacturers. This, they had to admit later, turned out to be an overwhelming amount of work. All the production pieces were wax cast by Bielawski and De Patta finished each one by hand.

De Patta made an enormous personal investment in the less expensive production pieces, but even at very low prices, the public did not accept her avant-garde designs. In one of her letters she wrote that ‘. . . the Purchaser’s taste is conditioned by the choice between one conventional design and another— just as bad.’ (De Patta 30) De Patta became frustrated by her inability to change the consumer’s buying patterns and must have been disappointed that the democratic principles on which she had based her life and work had not produced success. They gave up their production line in 1957.

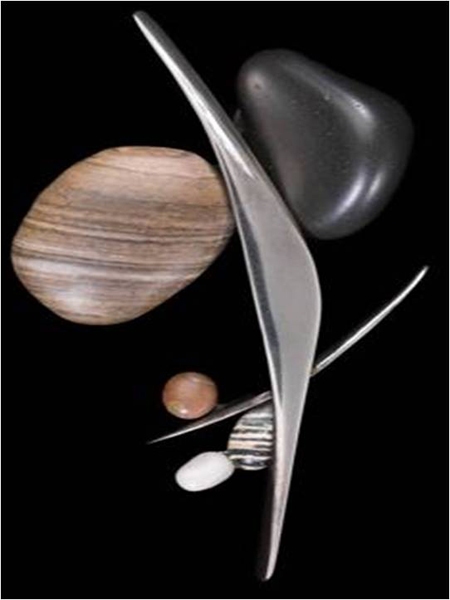

De Patta continued to be aligned with Moholy-Nagy’s constructivist ideas even into the 1960s. Her designs clearly were an inspired response to Moholy’s advice to ‘Catch your stones in the air. Make them float in space. Don’t enclose them.’ (Uchida 15) De Patta’s late pieces demonstrate the beauty she saw in simple river stones and beach pebbles. She collected them in large numbers to create her so-called Sweater jewelry. De Patta designed them to be worn either as a pin or as a pendant when a chain was attached.

Margaret De Patta’s art reflected constructivism’s treatment of space, light and motion and her life reflected the democratic ideals of the Bauhaus, which were innately her own from the very beginning. Her iconic works are as timeless and as vital today as when they were first made.