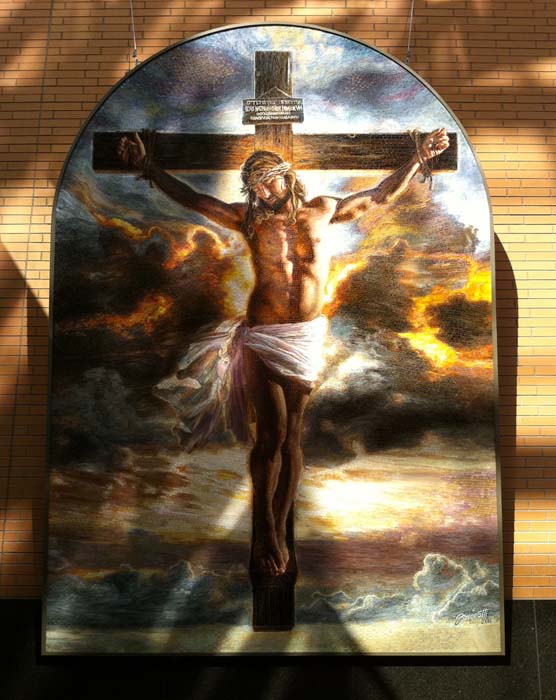

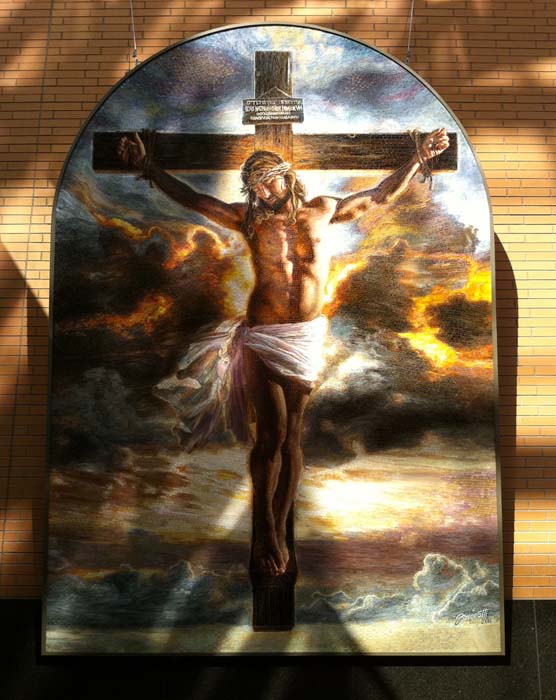

The top-prize winners over the past three years have been highly technical and competent works displaying a mastery of medium and an understanding of how to illusionistically render a subject in two-dimensions. In the contest’s first year Ran Ortner’s 19-foot wide, photo-realistic, oil-on-canvas rendering of ocean surf entitled Open Water No. 24 took top honors. Chris LaPorte’s 2010 winning entry Cavalry, American Officers, 1921 was again a 28-foot wide realistic rendering, this time graphite on paper. Taken together with 2011’s winner, Crucifixion by Mia Tavonatti (previously mentioned), a pattern emerges that clearly posits demonstrable skill, labor and scale as the most important criteria in the selection process. It is my contention that these works were chosen because the public generally understands technical skill, labor-hours and scale as objective standards by which to evaluate works of art. It is often through a combination of technical skill, time and ambition that a good artist can create a transcendent work that speaks to a broad audience or else commands a powerful emotive response. This is clearly the case with Ortner’s Open Water and Tavonatti’s Crucifixion, while LaPorte’s Cavalry relies more on romantic patriotism than a sense of sublime awe.

One thing that should be noted here is that certain displays of technical skill are not as discernible by the general public. This is something many bench jewelers know well. The inability of their clients to understand the skill involved in jewelrymaking can sometimes breed doubt, skepticism and derision. The same could be said of auto-mechanics. In general, the more esoteric a branch of manual knowledge and the further removed it is from the everyday experience of the public, the less ability it has to garner support in a competition like ArtPrize. Here, I think of West Michigan’s own David Huang, who indisputably creates some of the most technically virtuosic holloware in the world today. Displayed prominently at the Grand Rapids Art Museum (one of the competition’s most coveted venues) Huang showed a group of 21 vessels entitled Numinous Community, which demonstrated both the depth and breadth of his work. The immaculately raised, chased, rimmed, gold-leafed and patinated vessels ranged from 4 to 18 inches. Huang received much attention for his efforts, but despite his prominent billing did not make the top ten for the third year running.

In the case of past winners, the general public understands the basic mechanics of painting, either through their primary experience or else through contact with painting in film and media. The same is true of pencil-drawing; most people have direct experience with trying to draw something in pencil. General experience – with a pencil perhaps – teaches that it is more difficult to represent something accurately, in proportion and perspective, than to create an abstract composition. Therefore, works like Cavalry and Open Water are intuitively, qualitatively and objectively better in the public’s mind because they are difficult to achieve. This is the essence of the skill-based conception of craft.

This phenomenon – of art parading itself as craft – is something I have never seen before. In ArtPrize the hierarchy of the art world seems to collapse. As I have described, works of art appealed to the public through their craft virtue, while craft-based works appealed in their materiality, honesty and authenticity. Even works of outsider art and folk art appealed in their time-intensive creation, quirkiness and accessibility. The virtuous public eschewed any inherent genre hierarchy that might exist in form or typology. Perhaps Robert Shangle’s Under Construction, a performance of two living statues that was a top-ten work in 2011, best exemplifies this egalitarian leveling. Though craft’s vernacular appeal is surely not news, it is heartening to see such a palpable demonstration of craft’s democratic power in action.

Noticeably absent from the competition were works that dealt with the body as a primary concern, jewelry included. As a medium, jewelry invites close examination, investigation and even physical interaction. In a competition, where scale and technical accessibility seem to reign, the imperative of intimate and bodily works was certainly subdued. Making a brooch or necklace to compete with a monumental photo-realistic rendering would indicate a fundamental misunderstanding of the strength of the jewelry medium and its role in our culture. It is ironic, then, that jewelry remains one of the most ubiquitous forms of cultural production, yet seemingly does not enjoy the popular support of painting, drawing or even glass mosaics. It is good to know that as a concept craft is accessible even if, in manufacturing and in scale, jewelry is the least relatable manifestation of the genre.

The top-prize winners over the past three years have been highly technical and competent works displaying a mastery of medium and an understanding of how to illusionistically render a subject in two-dimensions. In the contest’s first year Ran Ortner’s 19-foot wide, photo-realistic, oil-on-canvas rendering of ocean surf entitled Open Water No. 24 took top honors. Chris LaPorte’s 2010 winning entry Cavalry, American Officers, 1921 was again a 28-foot wide realistic rendering, this time graphite on paper. Taken together with 2011’s winner, Crucifixion by Mia Tavonatti (previously mentioned), a pattern emerges that clearly posits demonstrable skill, labor and scale as the most important criteria in the selection process. It is my contention that these works were chosen because the public generally understands technical skill, labor-hours and scale as objective standards by which to evaluate works of art. It is often through a combination of technical skill, time and ambition that a good artist can create a transcendent work that speaks to a broad audience or else commands a powerful emotive response. This is clearly the case with Ortner’s Open Water and Tavonatti’s Crucifixion, while LaPorte’s Cavalry relies more on romantic patriotism than a sense of sublime awe.

One thing that should be noted here is that certain displays of technical skill are not as discernible by the general public. This is something many bench jewelers know well. The inability of their clients to understand the skill involved in jewelrymaking can sometimes breed doubt, skepticism and derision. The same could be said of auto-mechanics. In general, the more esoteric a branch of manual knowledge and the further removed it is from the everyday experience of the public, the less ability it has to garner support in a competition like ArtPrize. Here, I think of West Michigan’s own David Huang, who indisputably creates some of the most technically virtuosic holloware in the world today. Displayed prominently at the Grand Rapids Art Museum (one of the competition’s most coveted venues) Huang showed a group of 21 vessels entitled Numinous Community, which demonstrated both the depth and breadth of his work. The immaculately raised, chased, rimmed, gold-leafed and patinated vessels ranged from 4 to 18 inches. Huang received much attention for his efforts, but despite his prominent billing did not make the top ten for the third year running.

In the case of past winners, the general public understands the basic mechanics of painting, either through their primary experience or else through contact with painting in film and media. The same is true of pencil-drawing; most people have direct experience with trying to draw something in pencil. General experience – with a pencil perhaps – teaches that it is more difficult to represent something accurately, in proportion and perspective, than to create an abstract composition. Therefore, works like Cavalry and Open Water are intuitively, qualitatively and objectively better in the public’s mind because they are difficult to achieve. This is the essence of the skill-based conception of craft.

This phenomenon – of art parading itself as craft – is something I have never seen before. In ArtPrize the hierarchy of the art world seems to collapse. As I have described, works of art appealed to the public through their craft virtue, while craft-based works appealed in their materiality, honesty and authenticity. Even works of outsider art and folk art appealed in their time-intensive creation, quirkiness and accessibility. The virtuous public eschewed any inherent genre hierarchy that might exist in form or typology. Perhaps Robert Shangle’s Under Construction, a performance of two living statues that was a top-ten work in 2011, best exemplifies this egalitarian leveling. Though craft’s vernacular appeal is surely not news, it is heartening to see such a palpable demonstration of craft’s democratic power in action.

Noticeably absent from the competition were works that dealt with the body as a primary concern, jewelry included. As a medium, jewelry invites close examination, investigation and even physical interaction. In a competition, where scale and technical accessibility seem to reign, the imperative of intimate and bodily works was certainly subdued. Making a brooch or necklace to compete with a monumental photo-realistic rendering would indicate a fundamental misunderstanding of the strength of the jewelry medium and its role in our culture. It is ironic, then, that jewelry remains one of the most ubiquitous forms of cultural production, yet seemingly does not enjoy the popular support of painting, drawing or even glass mosaics. It is good to know that as a concept craft is accessible even if, in manufacturing and in scale, jewelry is the least relatable manifestation of the genre.